Juliet Carpenter, Christina Horvath and Ségolène Pruvot on celebrating and legitimizing voices from the banlieues against a backdrop of police violence in France

n the 29th June 2023, the conference and festival “Literature in the Margins” opened in Aubervilliers/Saint-Denis. This four-day event, coordinated by European Alternatives, the University of Bath and the University of Oxford, brought together prominent artists, writers, filmmakers, publishers and thinkers with postcolonial and banlieue roots to explore the specific difficulties with gaining recognition in French public space and the publishing industry. Balla Fofana, Katouar Harchi, Fatima Ouassak, Diaty Diallo, Mabrouck Rachedi, Mamadou Mahmoud N’Dongo, Mame-Fatou Niang, Insa Sané, Paula Anacaona and Nadia Bouchenni were among the speakers. The whole programme can be consulted here.

The Festival opened two days after a young man from Nanterre, Greater Paris, was shot by a policeman. The killing of Nahel M. created a wave of revolt and contestation for more than five nights, mostly emanating from young people residing in the French “banlieues”. French society was – once again – violently confronted with its contradictions: the polarisation between those who saw the expressed discontent as legitimate protest against state violence and those who condemned it as rioting or a street mob. The conference and festival, taking place against a backdrop of daily protests and curfews, contributed to the debate, by providing a space where emotions triggered by the events could be expressed and criticism of systemic discrimination against voices from the margins could be articulated. This criticism was primarily focused on the exclusion of artists from French public debate, on the grounds of social class, gender, and racial and linguistic minority status.

The words of the authors resonated deeply, like for instance those of Mabrouck Rachedi, or Diaty Diallo. Both authors have published novels, 20 years apart, which build a narrative echoing the events of recent weeks in Greater Paris, (“Le poids d’une âme” by Mabrouk Rachedi in 2006, and “Deux seconds d’air qui brûle” by Diaty Diallo in 2022). Both relate to police killings that lead to violent contests in the streets, mirroring the unrest that was sparked by the killing of Nahel M. in Nanterre. Similarly, the work of Katouar Harchi, notably in her book “Comme nous existons” (2021) highlights similar instances of police violence.

The Festival was grounded in Saint-Denis, just north of the city of Paris. Saint-Denis is emblematic and paradigmatic of the French ‘banlieues’. The stigma attached to its name and post-code –‘93’– in popular representations makes it for many synonymous with poverty, violence, a disregard for the rule of law and more recently, terrorism. As organisers of the Festival, who have developed strong links with the place, we know however that a closer look at the city – at its history and current activities – tells another, and much more complex, story. It was a deliberate choice to ground the Festival in this area, also known as the birthplace of some of the most iconic French Rap bands and most famous slammers over the past decades, and also the place of residence of some of the writers present at the Festival. Unfortunately, as the result of curfews and institutional caution, some of the evening events had to be postponed.

The Festival “Literature in the Margins” was inspired by FLUP – the Literary Festival of the Urban Peripheries, co-founded in 2012 by Julio Ludemir and Écio Salles in Rio, Brazil.. FLUP, set up in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, showed that it was possible to destigmatise low-income neighbourhoods through cultural events and by supporting emerging authors, from first readings right through to publication. The comparative perspective with Brazil tells us that literary margins can be constructed in different ways. In France, centuries of political centralisation have long associated centrality with power and distance from the centre with subordination, turning marginality into a stigma that writers seek to reject at all costs. However, as Brazilian researcher and keynote speaker at the conference, Paulo Roberto Tonani do Patrocínio pointed out, marginality can also be claimed as a desirable literary label, a source of collective identity and political positioning. His essay with the provocative title “O que há de positivo em ser marginal?” (“What’s positive about being marginal?” (2011), reminds us that the Brazilian avant-garde movement known as “marginal literature”, which emerged from the suburbs of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in the 1990s, created a counter-discourse, a sense of self-affirmation and protest, and a new aesthetic.

In France, even some universally acclaimed writers have declared themselves rejected or treated as illegitimate. For example, in her acceptance speech for the 2022 Nobel Prize, Annie Ernaux spoke of her desire to become a writer to “avenge her class”, believing that “becoming a writer, at the end of a line of landless peasants, workers and small shopkeepers, people scorned for their manners, their accent, their lack of culture, would be enough to repair the social injustice of birth and erase centuries of domination and poverty”. At the same time, established and internationally acclaimed writers such as Faïza Guène, translated into 26 languages and recently named in the “International Writers programme” by the British Royal Society of Literature, express the feeling that they are not fully recognised as French writers: “you can find yourself in this situation when you come from a working-class or even poor background, and […] you make a social or professional ascent, etc., and you don’t feel part of the group”.

With the conference and festival, the curators were particularly keen to explore the positive potential of the margins as creative spaces and resources for producing radically new aesthetics and forms. The event programme included presentations by researchers, interviews with writers, film screenings, creative performances, round tables with authors, and creative workshops. Over the course of the four days, the programme included contributions from a number of artists: Julio Ludemir, author and co-founder of the FLUP festival, Geovani Martins, a leading author discovered by FLUP, author and publisher Paula Anacaona, who translated and published texts by marginal Brazilian authors, as well as Afro-feminist theoretical texts, as well as director Keira Maameri, comic artist Bethet One, novelist and slammer Insa Sané, the founder of the Dictée Géante and novelist Rachid Santaki, authors who have just published their first novels such as Balla Fofana and Diaty Diallo, author of a novel about police violence in the suburbs, and established authors such as Mamadou Mahmoud N’Dongo and Mabrouck Rachedi, as well as ecologist Fatima Ouassak. The programme also included street theatre, workshops, and moments of collective sharing of food. The festival provided an opportunity for participants and presenters alike to take a stand against discrimination, racism and police violence, against the backdrop of the unrest, anger and bitterness that spread around France, expressed both peacefully and violently, in the streets of large and small cities alike.

The death of Nahel M. was a stark reminder of the challenges facing French society: a demonstration of the difficulty for French society to accommodate diversity beyond the promises of undifferentiated universalism; a demonstration of the lack of understanding of the lives of those who are discriminated against, based on their place of birth, place of residence, colour of their skin or simply due to their names. Emotion was strong. Beyond sadness and solidarity with the family of the deceased, and with all those who experience racist discrimination on a daily basis, the festival organizers and participants also shared some of the anger felt throughout France. This was prompted not only by the killing of a racialized young man by the police, but also by the statement published by police syndicates the day after the killing, and a sense of disgust at the online fund-raising, which raised over €1 million for the family of the policeman, fuelled by supporters of the extreme-right. The killing took place in a general context of increased police violence against demonstrations, including most recently, the violent police repression of the demonstrations against the pension reform, and the ecological protests in Sainte Soline. Happening against this background, the festival seemed even more relevant. On Friday 30 June, even the UN called for France to act on systemic violence and racism in the police.

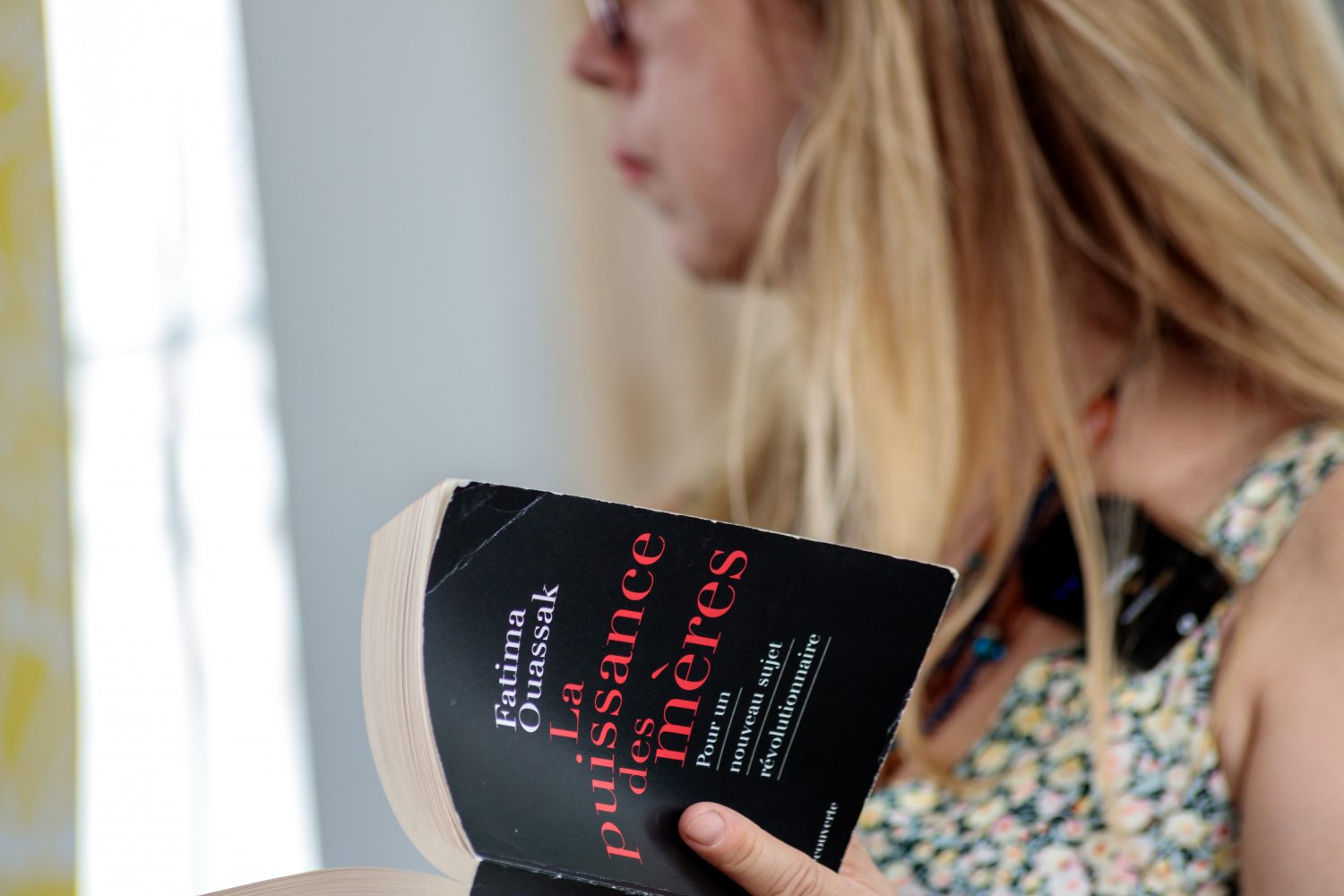

Just as parents in the banlieues were asked by the government to keep their children and young adults at home and threatened to be made financially responsible for damage, the exchange with Fatima Ouassak provided the possibility to discuss the role assigned to parents as “buffer” between the state and their children, as taming agents to make them accept forms of violence and police repression on the street. Fatima Ouassak rightly asks in her book “La Puissance des Mères” (2020) how parents are supposed to protect their children: is it by making them accept situations that seem unjust or is it by allowing them to form a critical mind and express discontent? Without justifying violence or destruction, Ouassak’s question highlights the difficult position of parents of children who live in working-class neighbourhoods and have little access to paths towards social mobility, outside some limited, but widely publicized, exceptions, which are taken as examples to point to what is presented as “the individual failures” of others, rather than highlighting systemic failures to address social and economic exclusion.

Just before attending the festival, the writer and ecologist Katouar Harchi, published a tribute in the magazine Télérama, which was read out at the festival. A few of the sentences of this piece are still acutely relevant and worth reflecting on, after the apparent return to peace in the “banlieues”. Katouar Harchi writes:

In France, racialized men from working-class groups are being expelled from the human community – the moral community. Animalised. And made killable… So before Nahel was killed, he was killable… Racism weighed on Nahel. He was exposed to it. He ran the risk of falling victim to it… I would like to say that we who refuse the order of racism and its violence will not go quietly, we will not go peacefully, we will not go without revolt, we will not go without struggle, without resistance, we will not go without organisation, without gathering, without demonstration, we will not go without truth, without justice… equality cannot be white. Equality is for all.

Despite order having been restored, the seeds of unrest and polarization are being fuelled everyday by the refusal of French society to face seriously the intertwining of racism, police violence and deep social and economic inequality. Little is done to act on the various forms of discrimination that are imposed on a large part of the French society, kept at the margins of affluent cities and of economic and symbolic power.

The current French government has been turning a deaf ear to various forms of expressions of discontent – that of racialized minorities, that of workers from less affluent and rural areas gathered in the gilets jaunes (yellow vests), women losing out more than others with the pension reform, young (and less young) people worried about the environment. It has answered with demonstrations of force, intimidation, and disregard. By perpetuating symbolic violence towards those who are at the margins of power, by nourishing resentment and contempt towards those expressing discontent, it contributes to disillusionment towards politics and to distrust in institutions and elections. At a time in which the extreme right-wing rhetoric and ideas are gaining ground and in a country in which the political parties are as weak as they currently are in France, this is a very dangerous game.

The festival “Literature in the Margins” which attempted to reframe public discourse was a modest but valuable attempt to reconnect the periphery with the centre by drawing attention to positive representations of the margins and to document and highlight the creative potential of those who are not yet at the centre, but who claim and deserve a place in public debate and a more equal share of power relations.

Dr Juliet Carpenter is Director of Research at the Global Centre on Healthcare and Urbanisation (GCHU), at the University of Oxford. Her research interests lie at the intersection of urban geography and the humanities, focusing on unheard voices in peripheral urban spaces.

Dr Christina Horvath is a senior lecturer in the Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies at the University of Bath with research interests in contemporary urban issues.

Ségolène Pruvot is a Director of European Alternatives. Trained as a political scientist and urban planner in France, the UK, and Germany, she has developed extensive experience in designing and implementing transnational participative artistic and cultural programmes.