by Sofia Rosano and Ilaria Cascino

When it comes to youth and politics, a complex relationship emerges. Frantz Fanon said that every generation has a historical mission, and youth have never shied away from theirs – they protest, propose, and envision a different world.

Yet, according to a recent study by the Osservatorio Giovani, most young people feel excluded from politics, which they see as distant, self-referential, and unable to address today’s urgent issues. This is compounded by a paternalistic narrative that labels youth as “lazy” or “disinterested.” A former Italian Minister of Economy once dismissed youth unemployment by calling young people too “choosy”.

The paradox is evident: while youth are accused of disengagement, politics does little to involve them. Power remains concentrated in older generations – Italy’s current leadership has an average age of over 50.

So, how do we mend this gap? Should young people push forward with energy and patience, or should institutions make the first move by truly listening?

A possible answer lies in southern Italy, particularly Sicily – an island often seen as deeply disillusioned with politics. Here, distrust in institutions is widespread, and historically, the state’s presence has often been weak or ineffective.

However, Youth Councils (Consulte Giovanili) offer a way to reconnect young people with governance. These bodies, established within local administrations, aim to engage youth in policymaking and provide concrete tools for civic participation. They can act as a bridge between new generations and local institutions, enabling young people to take an active role in public life and fostering a more inclusive democracy.

The island of those who stay

Sicily is the land of sun, sea, art, and culture – or at least, that’s what the clichés say. But it is also one of the most economically depressed regions in Europe, ranking among the lowest in all well-being indices, with widespread youth distress caused by poverty, chronic unemployment, low literacy and education rates, and no concrete vision for the future.

No need for statistics or reports to notice it: a walk through its crumbling streets, a glance at its deteriorating infrastructure (including the failing water system behind the recent water crisis), or an attempt to access its minimal public services – from healthcare to transport – is enough. For those who live here, the feeling is of inhabiting a land that seems hostile to its own people.

And who feels this hostility more than young people? Without real opportunities or the chance to envision a dignified future in their homeland, emigration becomes the only option. Some estimates speak of nearly 50,000 young people leaving each year – not out of choice or wanderlust, but out of silent necessity. Thousands of young men and women, unable to build a future in their own region, cross the Strait of Messina with a one-way ticket. A tragic phenomenon that begins early, with many Sicilians leaving right after high school to pursue university education that offers better job prospects.

The result is devastating: a region that ages, empties, and risks becoming increasingly marginalized.

Yet, alongside the many who leave, there are those determined to stay – or return – and bet on their homeland. Despite the sacrifices and difficulties, some young people choose to remain and build a future where few have ever truly believed in one. But how can they make their voices heard within local institutions without facing the same disappointment?

In recent years, Sicily has seen a true boom in Youth Councils. More and more municipalities are establishing them, with at least 123 councils currently active out of 391 Sicilian municipalities. In some cases, they have even formed territorial networks, such as the Consulte Madonite, which recently united into a single youth-led project for the future of Sicily’s inland mountain areas. The phenomenon became so significant that, in 2019, the Sicilian Regional Government took notice, attempting to create a regional youth council to bring local demands directly to the Sicilian Parliament – a project that ultimately failed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the heart of this movement is the recognition, even by institutions, that giving young people space is essential to prevent further depopulation. However, there is a lingering risk that these councils remain empty shells – mere tokens of old politics designed to give youth the illusion of influence without granting them real decision-making power. The key lies in the dialogue between young people and institutions, in filling these spaces with genuine participation, rooted in the belief that youth can be a true force for change in society.

Building youth communities: the case of Monreale

The example we want to share takes place in Monreale, a town overlooking Palermo, and traces a path of growth that can be traced back to the 1970s – when, on a narrow staircase in a working-class neighbourhood, a woman decided to open her home to the world. Since then, the youth of this town have no longer been just an age group but an active force in society, embarking on a journey whose fruits can be seen today (though certainly not only) in their institutional legitimacy through an important tool: the Youth Council.

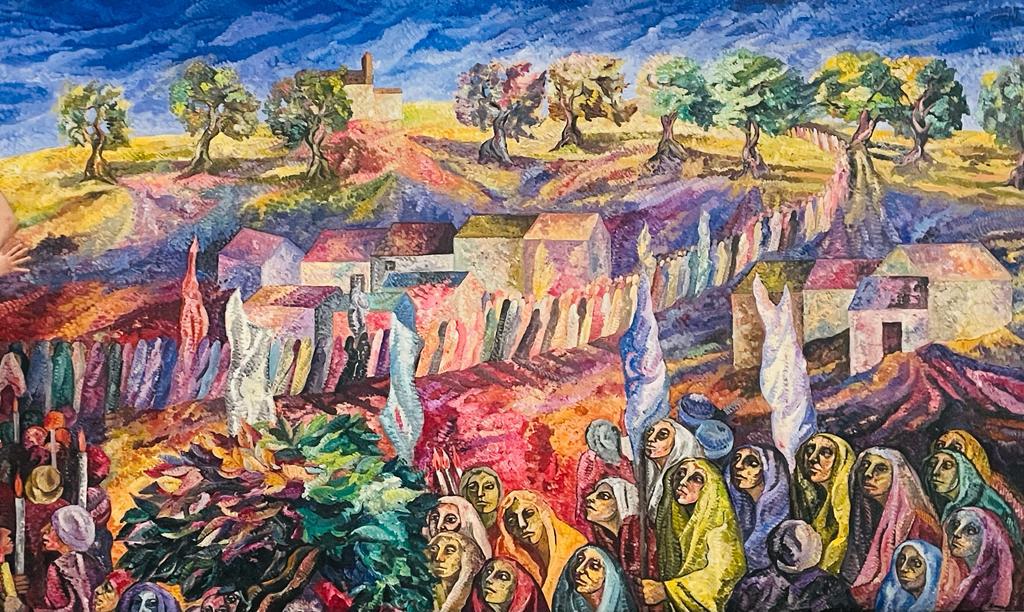

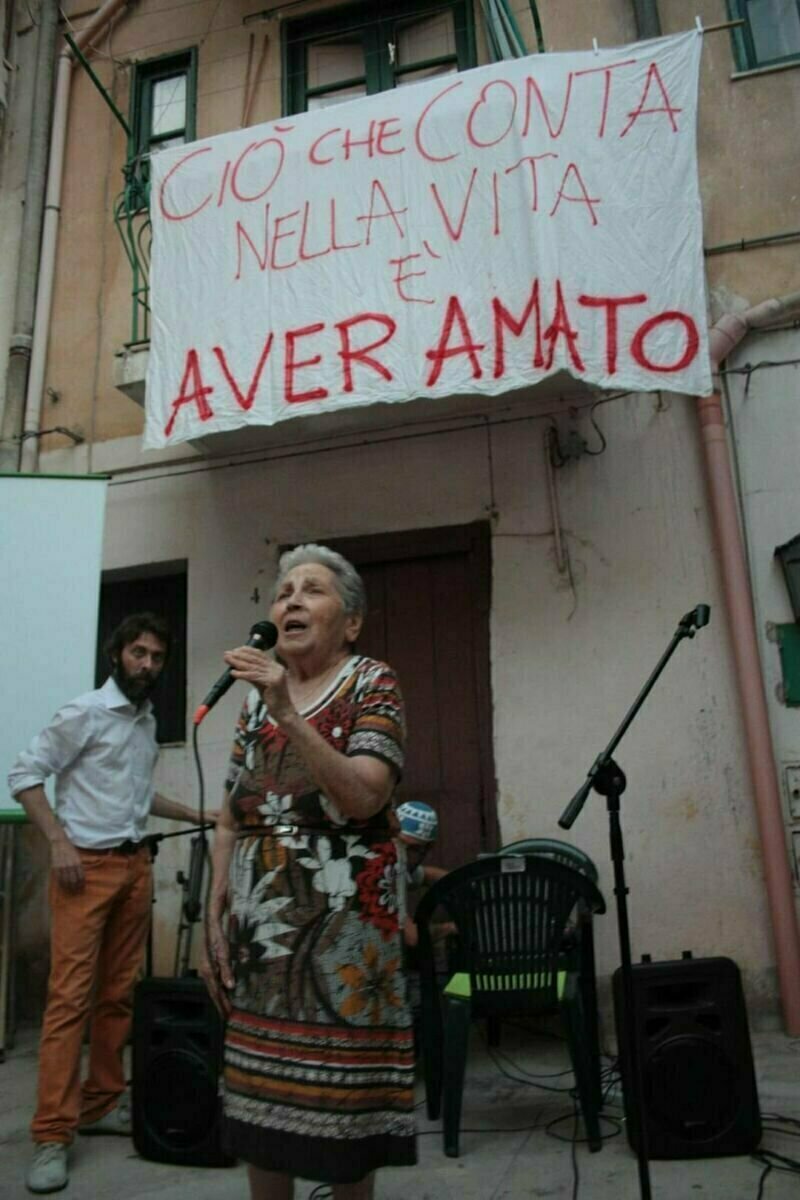

That woman was Sarina Ingrassia (1923 – 2015), a pioneer of social activism in Monreale. Founder and soul of the association Il Quartiere, Sarina began working in the Bavera district in 1975, foreseeing the importance of grassroots mutual support. From the very beginning, active participation and cooperation proved to be the best means of bridging the gap between citizens and politics and achieving social justice.

For over forty years, Sarina welcomed into her home anyone affected by poverty in any form, without judgment – only out of dedication. In her diary, she wrote: «Since my youth, I have found the purpose of my life in ‘meddling’ with the needs of others, and in order to belong to everyone, I decided not to belong to anyone. […] Around my personal choice, others have joined in this service, and above all, different generations of young people have alternated over time. Today, as they continue their journey, they find themselves holding responsibilities for the community».

Above all, she built a network of young people from diverse backgrounds who became the foundation of the project she envisioned. In her home, they helped organize activities – supporting children facing educational and cultural hardships, families in socio-economic distress, single mothers, and people struggling with addiction. They learned, reflected on the complexities of their social reality, and approached volunteering as «the highest form of politics».

The relationship between volunteering and institutions was one of frankness: institutions were fundamental and necessary to combat economic and cultural poverty, but they often became the target of urgent appeals to do more, stepping in where associations found themselves alone.

A decade after her passing, Sarina remains a model for those who have inherited her legacy, her vision of volunteering, and her approach to politics. As Émile Durkheim suggested, the actions of the young people who open their doors daily demonstrate how society continually regenerates its cohesion – almost as if it were a generational necessity, activating all the resources needed to reduce vulnerability and prevent exclusion.

Though in a different form, the values passed down by Il Quartiere and Sarina have shaped Monreale’s associative fabric, leading to the rise of new initiatives over the years. The community has been revitalized by young people who have carried this legacy forward for more than four decades. Among the most significant examples is the emergence of grassroots collectives and committees, formed spontaneously as an expression of youth and territorial self-determination.

One such example is the Arci Link collective, which, between 2017 and the COVID-19 pandemic, managed to open a youth center in the area. They organized events like the temporary occupation of abandoned soccer fields, transforming them into spaces for artistic and musical performances to demand their reopening. They also carried out other initiatives to highlight the need for dialogue with associations and local institutions. Another is Comitato Pioppo Comune, which has become a cornerstone of social activism in the Pioppo district, working on urban regeneration, environmental protection, advocating for the reopening of a local school, and opposing the construction of a private cemetery in a crucial environmental area.

The world of associations remains a home for those who recognize and wish to explore their potential, who are aware of their role within their community, and who choose to take a stand for themselves and others. Intergenerational exchange and the promotion of critical thinking enhance participation as a shared responsibility.

Through this process, horizontal and community-driven practices lay the groundwork for strong alliances. The enthusiasm for collaboration with socio-cultural organizations, combined with a willingness to build networks with local third-sector entities, public and private institutions, schools, political bodies, and the Church, helps restore services that address the specific needs and aspirations of today’s youth.

Just as inspiring—though often marked by tension – is the relationship between these grassroots movements and local institutions. While young activists continuously push for action and engagement, institutions are not always willing or able to listen. Yet, it is precisely within this dynamic of confrontation and dialogue that the most meaningful change can emerge.

Youth Councils as a ground for reconciliation

Thanks to the spirit that Sarina instilled in young people long ago, today in Monreale, they benefit from an accessible, active institutional framework that is open to the exchange of project proposals. This current situation did not materialize by a stroke of fate but is rather a first milestone, the result of a participatory process and dialogue with the Department of Youth Policies and the public administration. This has led to the recognition of social commitment and activism through the establishment of the Youth Council.

This step finally marks an initial opening towards younger citizens and greater collaboration in gathering resources and tools useful for the development of their aspirations.

Established in 2023, the Monreale Youth Council is designed from its very regulations as an inclusive space: open to all residents under the age of 30 without requiring any “endorsement” from third parties, it includes young people from different areas of the municipality (one of the largest in Italy!). It also grants automatic membership to student representatives, acknowledging their right and duty to be part of the administrative system. Furthermore, it has the possibility of having its own budget, allowing members to allocate funds for events and initiatives at their discretion.

The council’s assemblies take place in the Council Chamber, where the municipal council meets. This setting offers both the privilege and the responsibility of sitting among the benches of the institutions representing the territory. These meetings serve not only as opportunities for dialogue among young people, council members, and anyone interested in participating but also as moments of direct engagement with local institutions. The Youth Policy Councillor attends these meetings, proposing initiatives and responding to the council’s inquiries.

Since its inception a year and a half ago, the Youth Council has carried out initiatives that address the needs and proposals of its young members in various forms: theatrical performances, musical events, nature excursions, book presentations, and solidarity initiatives. The council has participated in regional projects and calls for funding, promoted voter participation in the European elections, and organized career and university orientation programs.

Recently, a study group on Danilo Dolci was also established, remembering this key figure in Sicilian history and his pedagogical influence, which is acknowledged in this edition of the Journal of European Alternatives. Other initiatives have been aimed directly at the local administration: through the project “Monreale is not a town for young people”, feedback was collected from high school students on what they believe is missing for young people in the city. The campaign “389 good reasons to increase AMAT bus routes” proposed an expansion of the local public transportation service. Additionally, by leveraging a municipal project for libraries, a public call was launched to involve citizens in the participatory purchase of books.

A key tool in engaging with young people and the broader community has been the strategic use of social media (IG: @consultagiovanilemonreale; FB: Consulta Giovanile di Monreale). Through videos, content creation, and regular updates, the Youth Council amplifies its voice and ensures that assemblies and initiatives receive maximum visibility. Social platforms serve as a bridge between young people and institutions, fostering greater participation and making sure that local issues are heard loud and clear. Every assembly is advertised online, ensuring transparency and accessibility.

Moreover, the Youth Council actively collaborates with numerous local organizations, cultural associations, the Pro Loco, and other youth councils across Sicily, fostering networks and reflecting on new possibilities for action.

So, are Youth Councils truly the right ground for reconciliation between young people and institutions? It depends. It depends on young people’s ability to legitimize themselves, to engage in dialogue, and to enter unfamiliar and diverse spaces. It depends on institutions’ willingness to make room, to be honest, and to embrace change. The tool itself, like a needle, helps to stitch a tear: but it is up to our skills as tailors to sew the two sides together into unity.

We, the authors of this article, have experienced this journey firsthand. From the welcoming space of Sarina’s home to the council chamber benches, we have lived through the process that led to the establishment of the Monreale Youth Council. As President and Vice President of this institution, we have seen how grassroots engagement can turn into institutional recognition. It is precisely because of this experience that we have chosen to tell this story—to show that change is possible, and that young people, when given the right tools, can shape the future of their communities.

Ilaria Cascino is an art historian, curator, and socio-cultural worker with nearly a decade of experience in the third sector. In 2022, she founded )(, an Artist Run Space in the Capo district of Palermo. Her passion for new creative practices and contemporary languages stems from the peripheral contexts of the South, where underground production and socialization are key to cultural growth. Since 2023, she has been the VicePresident of the Youth Council of Monreale.

Sofia Rosano holds a degree in Political Science and Economics and is currently pursuing further studies to specialize in Political and Institutional Communication. Passionate about writing and journalism, and actively involved in the third sector, she has always focused on social issues, using her skills to give a voice to those in need. Since 2023, she has been the President of the Youth Council of Monreale.