By Lena Penšek

I saw the documentary No Other Land about a year ago, and it left me speechless. It was the first time that I have ever sat at a film screening where the whole audience was completely still, sitting in their chairs in silence for another fifteen minutes. When people started standing up, I felt like they burst a cloud of sadness and grief that was hanging above the theater.

The rain outside the theater that night felt poetic, as if trying to match our emotions, and I decided to walk home to have time to let information, feelings, and general disbelief sink in.

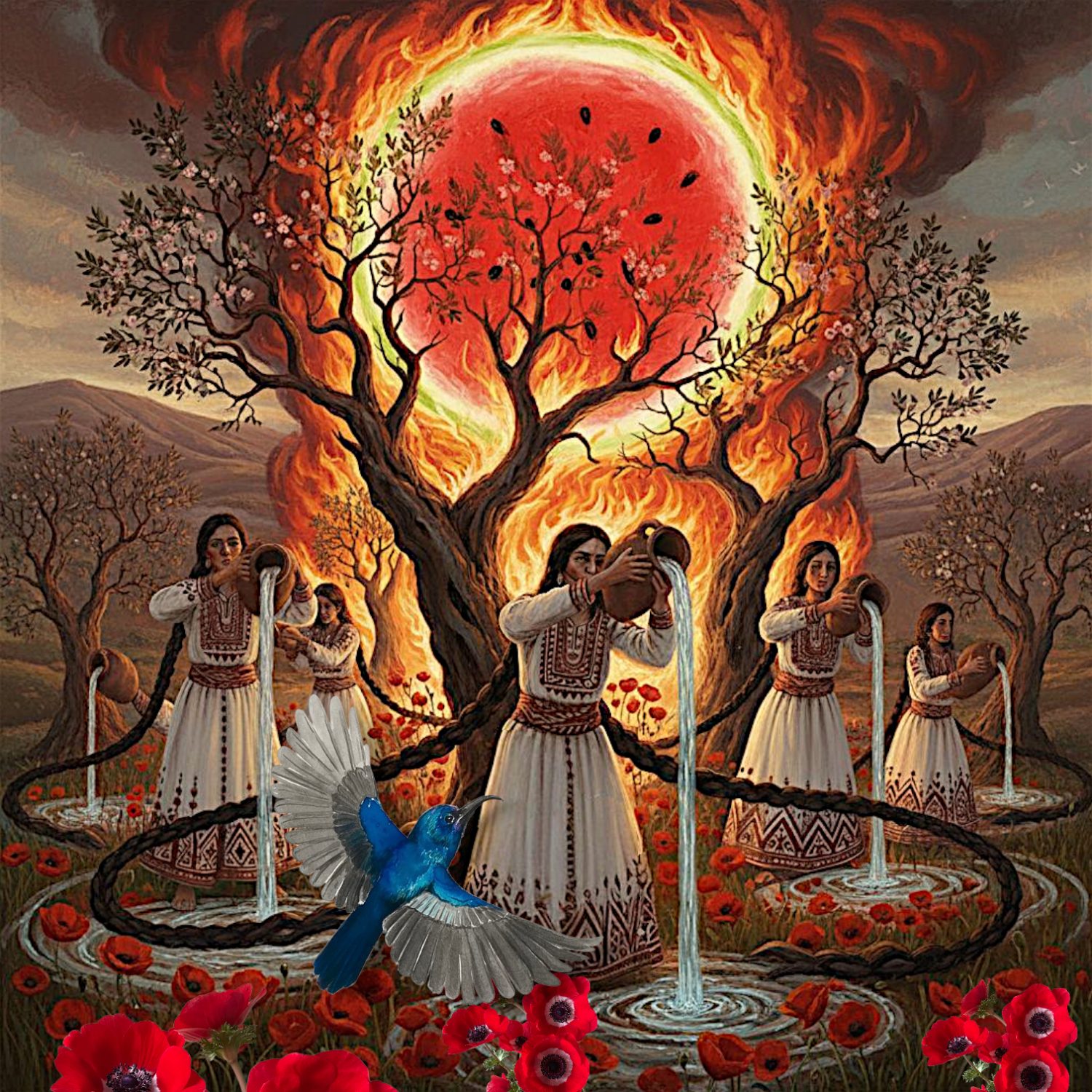

Braids on Fire © Sara Saif

This was the first time I really understood how people, once violently displaced and their homes forever destroyed, are so unlikely to return. And that land, now degraded and polluted, is so unlikely to ever be farmed by the same people in the same way ever again. The knowledge of working the land, passed down through generations, would not be passed down anymore and parts of it would forever be lost. Yet some people do return to their land, to love and care for it like their ancestors have for hundreds of years. Some people stay, they persist and they resist.

This article looks at the ecocide and environmental destruction in Palestine through an ecofeminist lens. It argues that the Israeli settler-colonial project is a project of imperialism, colonialism and capitalism,1 and that these are intertwined with patriarchal structures of society. Because it is a deliberate ecocidal project of destroying land and environment in Gaza and Palestine it is an assault on life itself.

This article is written in solidarity, not to speak on behalf of Palestinians, but to amplify their voices and highlight another perspective on the ongoing genocide. As a white Slovenian woman living in peace, I recognise my privilege and choose to use my time, energy, and platform to support and draw attention to the struggle of the Palestinian people.

An assault on life itself because it is an ecocide.

For more than a century, since the Balfour Declaration, the Israeli settlers have been actively and deliberately displacing Palestinians from their land by creating conditions that have made life in Palestine a constant struggle. As Dr. Mazin Qumsiyeh the founder and director of the Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability describes it: “Ecocide refers to severe, widespread, and long-term environmental destruction that undermines the ability of inhabitants to enjoy and sustain life.”2

The ecocide is not an accidental side effect of the genocide – its deliberate, systematic and just as intentional. It is destroying all, as defined by Vandana Shiva, “vital elements on which all life on Earth depends: water, soil, air, forest and, last but not least, climate.”3

After two years of constant bombing, Israel has, according to the official numbers, killed 10% of the population of Gaza.4 The majority of Gaza is under rubble and 98.5% of agricultural land has become unviable for cultivation.5 Orchards, greenhouses and vital crops are being completely wiped out, olive groves and farmers reduced to leveled earth, and soil and groundwater contaminated with toxins and munitions,6 to explicitly name just a few intentional ways in which Israel is destroying land in Palestine. This, on top of literally destroying villages with bulldozers and killing everything and everyone in their way, as seen in No Other Land, and the list could truly go on and on and on.

Environmental destruction is used as a weapon7 against Palestinians, it is a deliberate destruction of their entire social and ecological fabric, the basis of their livelihood, community and resilience.

An assault on life itself because it destroys what gives life.

Feminist writer and activist Ariel Salleh describes ecofeminism as “the only political framework … that can spell out the historical links between neoliberal capital, militarism, corporate science, worker alienation, domestic violence, reproductive technologies, sex tourism, child molestation, neocolonialism, Islamophobia, extractivism, nuclear weapons, industrial toxics, land and water grabs, deforestation, genetic engineering, climate change and the myth of modern progress.”8

In patriarchal capitalist society, ecological destruction on a mass scale, an ecocide, is just as acceptable as oppression against women. It is a society that does not need human emotions, feelings, morals or responsibility, but instead needs violence,9 and is a “system which promises a better life for all but ends in killing life itself.”10 Furthermore, constant colonisation is a necessary condition for capitalist growth in patriarchal society, and “without colonies, capital accumulation would grind to a halt.” 11 In this sense, the land, women and ‘others’ are in a capitalist patriarchy yet another colony, seen as raw material and for its passive function to produce and add value, instead of their power of creative regeneration.12

In ecofeminism, nature is understood as a living subject, not just a raw material – it is what gives and creates livelihood and forms the centre of the cultural fabric of a society – it is what gives life. Aggression and extraction of nature is an act of destruction of what supports livelihood, community, culture, peoples, of what gives and creates. And the regeneration of that land is a long process of recreation of life, not a sheer technological issue of clearing away the rubble, toxins and dead bodies left behind by war.

An assault on life itself because body is land.

Cuerpo-territorio – body-territory – is a decolonial ecofeminist theory and movement that emerged from Bolivia and Guatemala.13 It expands on the central feminist critique of Cartesian dualism – separation of mind and body. The critique that challenges false patriarchal binaries which associate the mind, reason, culture, subject as masculine, and body, nature, emotion, object as feminine.14 Cuerpo-territorio sees the human body and the land as inseparable and interconnected.

The intertwined forms of oppression against women – patriarchy, colonialism and extractivism – are extended in their oppression against nature. Just as women’s bodies are being oppressed, extracted from and overpowered, in the same manner nature’s land is subjugated in patriarchal capitalist society. What is the body of women is the land of nature. It is an oppression against what gives life. Thus, any deliberate destruction of land is destruction of life itself.

As the Indigenous lands of Abya Yala (a term from Guna language, used by some Indigenous people for Americas), where the concept of cuerpo-territorio emerged from, were colonised and extracted, the Palestinian land is also systematically targeted by extractivism and colonisation. And just like the Indigenous women’s bodies were battlefields of colonial control,15 Palestinians, too, are the subject of colonisation. They use their bodies to resist and fight against oppression. And the body, just like the land, becomes a political category – a place of resistance.

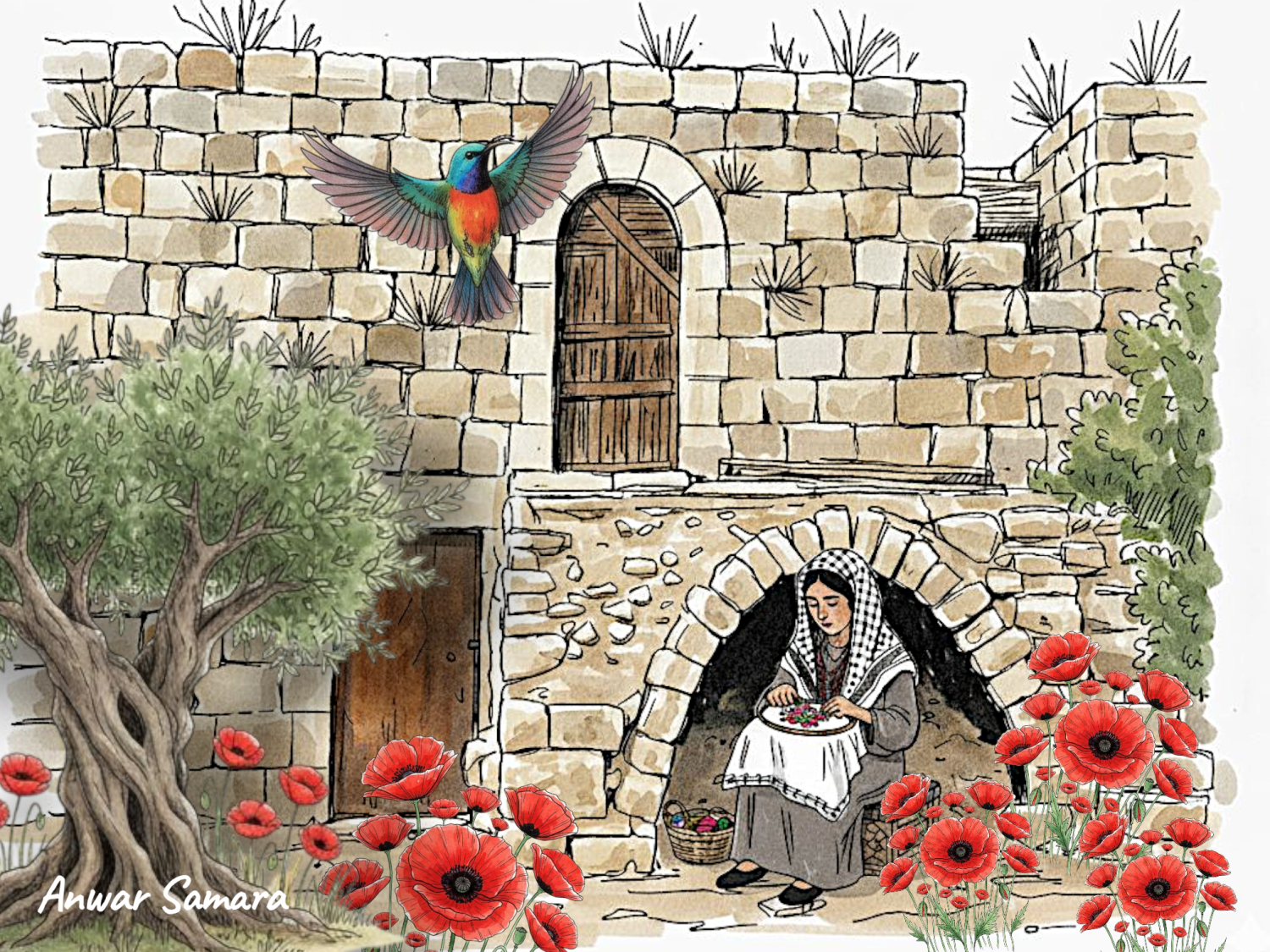

The Keeper © Anwar Samara

Their resistance is our resistance.

Palestinians continue to live with and through the land, cultivating, regenerating and growing life and through that use their body for resistance. In their action, they do not just resist Israel, they resist imperialism, colonialism, all systems of oppression and the patriarchal capitalist world system. Yes, the land is polluted, destroyed, and almost impossible to work on, yet people stay, people return. They continue to preserve and exchange seeds, pick olives, cultivate the land and grow life.

Palestine shows us the future that is on the horizon for everyone, if we do not resist and fight. As in the famous quote of James Baldwin, written to Angela Davis in the 1970s: “For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.”16

A Palestinian activist and friend, and I could not have put it better, said, “in many ways Palestine, and what is happening in Palestine right now, is the beginning of what will come in the future to everyone if we do not do major shifts around the world. Solidarity with Palestine right now is not about solidarity with the ‘other’, it is about how each and every person around the world is also at the core of the struggle. The front lines of the struggle are everywhere in the world right now.”

One year after seeing No Other Land I am turning that grieving silence of a rainy evening into an act of resistance. Because it is an assault on life itself, we should all turn our grieving silences into action. Because it is an assault on life itself, it is an assault on us all.

If you wish to stand in solidarity with the people in Palestine and Gaza, here is a list of a few farming initiatives, projects and mutual aid accounts that you can follow and contribute:

Om Sleiman Farm @omsleimanfarm

Dalia Association @daliaassociation.ps

Ard Alyas @ardalyas99

Nabat Eco Farm @nabatecofarm

Grassroots Gaza @grassroots_gaza

Water is Life Gaza @waterislifegaza

The Sameer Project @thesameerproject

Arab Group for the Protection of Nature @apnorg

Illustrations

The two illustrations in this article were made by two incredible Palestinian women.

The opening image

Title: Braids on Fire

Illustrated by: Sara Saif, a Palestinian illustrator.

The image shows Palestinian women wearing their traditional Tatreez dresses and holding the traditional clay jars in face of the occupation that is represented by the fire that is slowly destroying the eco system in Palestine represented by the palestinian poppy flowers, the Palestinian sunbird and the almond trees. The women represent the soft power that indigenous people of Palestine are using to get over the horror.

Sara is part of a Palestinian platform of women from all around Palestine that try to show their culture and sell their handmade products in Europe, especially Slovenia, to support their families and themselves.

You can support them by following their account and buying their products on Instagram: @holylandshopeu2.

Image 1

Title: The Keeper

Illustrated by: Anwar Samara, a Palestinian architect and urban designer based in Slovenia.

The illustration captures a moment of serene, traditional Palestinian life. Nature and culture exist in perfect harmony in front of a vernacular Palestinian stone house where the iconic olive tree and native poppy flowers frame the scene alongside the vibrant Palestinian sunbird. Central to the image, a woman, her head wrapped in a kufia, is deeply engaged in the meticulous art of Tatreez (Palestinian hand embroidery), weaving history and identity into every stitch.

The story of The Keeper:

In the Palestinian scene, we quickly realize that the question is not who is the Keeper, but what the act of keeping truly is. Is it the ancient olive tree, with its enduring roots, preserving the land itself? Or is it the bright poppy, insisting on its spring rebirth? Is it the vibrant sunbird carrying its song over the valleys?

Ultimately, the Keeper is not an individual or a single object. It is a shared, continuous force. It is the woman’s hands working the Tatreez, the strength of the stones, the resilience of the flowers, and the memory held by the earth, it is every single one and all of them together. The land keeps the people, and the people, in turn, keep the soul of the land.

- Hamza Hamouchene, Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation, Transnational Institute, 2025.

- Mazin Qumsiyeh, Ecocide and Resistance in Palestine, The Ecologist, 2025.

- Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993, 2014 Foreword, p. 28.

- Marium Ali, Alia Chughtai and Muhammet Okur, Two years of Israel’s genocide in Gaza: By the numbers, Al Jazeera, 2025.

- FAO, Land available for cultivation in the Gaza Strip as of 28 July 2025, FAO, 2025.

- Hamza Hamouchene, Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation, Transnational Institute, 2025.

- Donna Cline and Julia Tétrault-Provencher, Nature and Nurture: How War Weaponizes Gender and the Environment, Opinio Juris, 2025.

- Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993, 2014 Foreword, p. 7.

- Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993, 2014 Foreword, p. 22.

- Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993, 2014 Foreword, p. 23.

- Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993, 2014 Foreword, p. 115.

- Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993, 2014 Foreword, p. 60.

- Atamhi Cawayu and Sigrid Vertommen, Cuerpo-Territorio/Body-Territory, Kohl Journal, 2025.

- Val Plumwood, Feminism and the mastery of nature, Routledge, 1993.

- Atamhi Cawayu and Sigrid Vertommen, Cuerpo-Territorio/Body-Territory, Kohl Journal, 2025.

- James Balwin, An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis, The New York Review, 1971.