by Niccoló Milanese

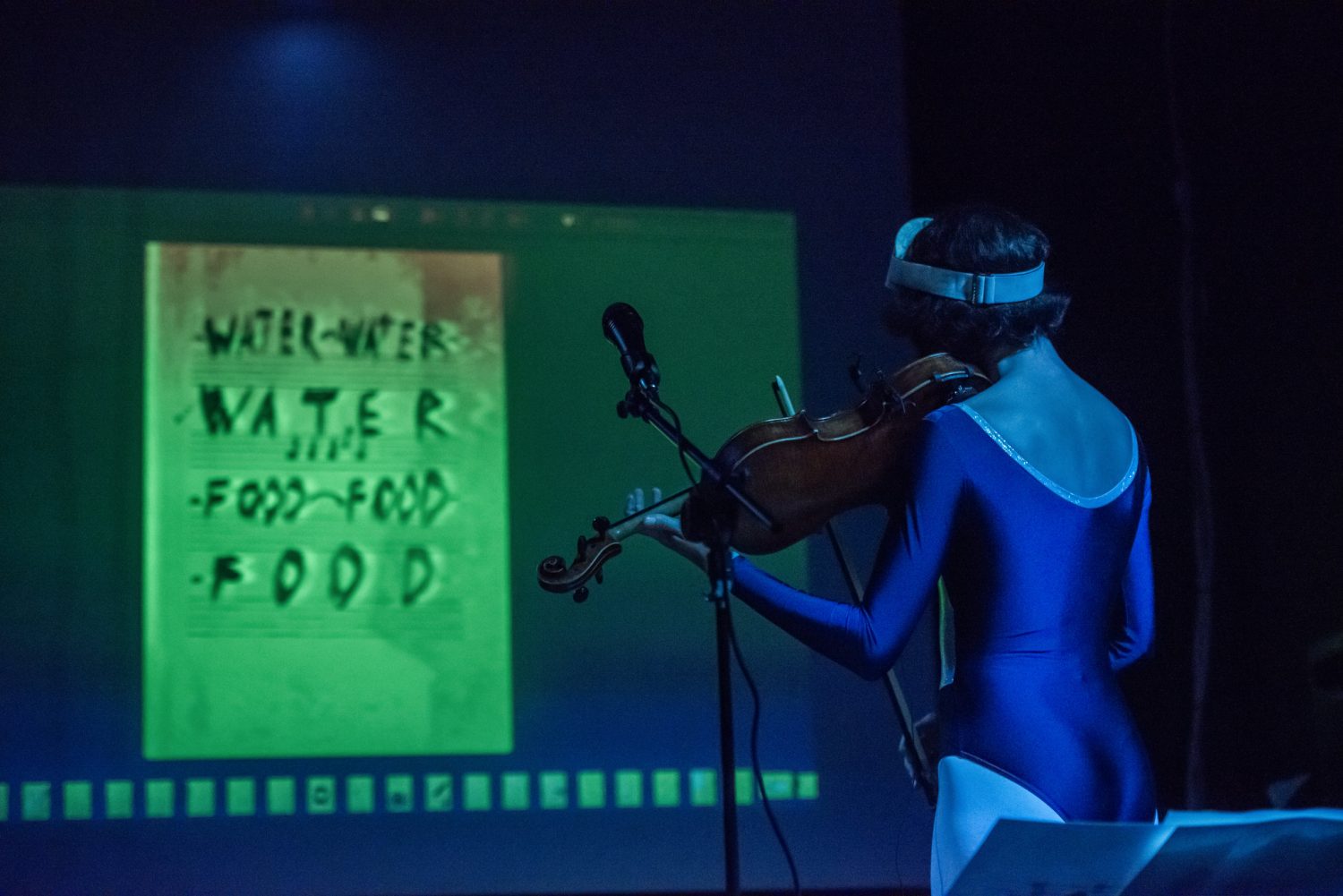

This article was originally published in Europa, written by one of European Alternatives’ founding directors, Niccoló Milanese, in 2008 on the relationship between arts and engagement in Europe before European Alternatives’ Cultural Congress in their 2008 London Festival of Europe.

This festival, and the ideas of imagination & culture being at the heart of creating a democratic and equal Europe, are a birthpoint to what has become Transeuropa festival in over 31 cities since 2007, and the objectives of the imagination stream.

From now on we live in imaginary communities. From when we cowered together in fear of the earliest thunderbolts of Zeus, the imagination has been the fundamental human faculty holding us together, but the specificity of large parts of the modern world is that we live in communities knowing full-well they are imaginary. The comparative ease with which many of us can cross geographical obstacles, globalised communications and the speed with which demographics is changing all call us to question what holds us together, and the only remaining answer is a shared imagination. To say that communities are imaginary is not at all to say they are false: on the contrary, it is to say they are absolutely real in virtue of shared imaginative spaces, the only spaces in which human communities can exist.

Europe is at the forefront of this global movement. Here, where there is so much by which communities could be defined and divided, when the defence and demarcation of different cultures, nations, religions, languages has taken up so much of our resources and blood, we are finally thrown forwards towards an identity no-one but wily old Zeus can fully capture: European. All attempts at saying what is or is not European necessarily fail, because they misunderstand the nature of the adjective: European is a way of carrying on, it is an endless process of self-creation. Some of us once made the disastrous mistake of thinking we had grasped for once and for all what Europe is and could impose it on others. From now on Europe can only progress by including its alterities. The imagination is the only structure which has the required property of being open to others whilst not destroying their difference. The imagination is the structure of negative capability.

The responsibility of those who tend to the imagination could not be higher. Not only do they have the responsibility for caring for the resources which hold our communities together, but they also have the responsibility for tending to those resources in such a way that we do not define ourselves against one another, that we do not foreclose differences too quickly. They have the responsibility for turning civilisations inside-out. The Europeans, living after and in spite of the many collapses of their own ‘civilisations’, have a historic duty.

Who are those who tend to the imagination? For us they are to begin with archetypes we have inherited from antiquity: the poet, the writer, the painter, the sculptor, the musician, the dancer, the philosopher, the critic. The imaginative tools we inherit as Europeans have been shaped and developed by these figures from the beginning of history, and they each carry a particular historical charge and character.

There are archetypes we have invented more recently, which are technological developments of the older archetypes: the photographer, the film maker, the TV producer, the radio script writer, the web designer. Technological developments in communications have opened up entirely new domains for the imagination to fill. The modern world is increasingly structured according to these new technologies of communication. Like all features of the modern world, that is a huge opportunity as well as a huge danger, which means to say it is a heavy responsibility. The danger is that the new technologies used inhumanely and unimaginatively tend to be alienating and solipsistic. The structures and prerogatives of technology are not automatically the same structures and prerogatives as those of human understanding, and they are by default private and personal, despite their apparent claim to opening intersubjective spaces. The new technologies of communication employ the modes of expression which belong to the arts, but do so impersonally. So long as the communities created via new technology remain merely ‘virtual’, they will not be human communities at all. They require the artist to make them real. The huge opportunity opened up by new technologies of communication is to give to the artist complete and direct influence over the state of real interpersonal relations by the exercise of his or her imagination. A feature of new technologies is that in using them each and every one of us is required to be an artist in this sense.

Europe is not a giant translation machine. For translation to be worthwhile there must be languages to translate between. The huge richness of the languages of Europe is an extremely good reason for being grateful that the language of Europe is not (only) translation. The languages we inhabit, which enter into us and structure the way we understand the world, are one of the ways our cultural and historical inheritance is given to us. Language is part of the living organism that we are, and requires the same attention, care, preservation and innovation. For a long time the languages of Europe have not belonged to any one people; in virtue of translation, but also in virtue of individual and collective multilingualism and as a side effect of domination. The search for a perfect language is perhaps a peculiarly European search, which has fascinated the most powerful of our thinkers and poets. But if they have been impassioned by this search, it is because they felt the richness of all the languages in Europe: the power of languages leads to awe, the diversity of equally rich languages to the idea of an even greater language.

The European fascination for languages tends to distract from other modes of communication in the arts other than literature-on-the-page. But many of the same questions can be put with regards to these other modes as are raised with regards to language: are there different ‘languages’ of sculpture or dance, which might vary throughout Europe? It is probably mistaken to imperiously extend the paradigm of language to cover these means of expression: language is one amongst them. At the very least we can say in general about the arts that there are different traditions, different costumes, different customs, different canons spread throughout Europe. And furthermore we can say that from the beginning, in Europe, these traditions and customs have been inescapably mixed and shared, even when the greatest efforts have been made to keep them ‘pure’.

But the contemporary European might regard the customs, costumes and canons he or she has ‘inherited’ as entirely foreign, and the idea of tradition something that has been overthrown by modernism. The apocalyptic visions of Europe’s cultural fate are well known. George Steiner often paints an image of TS Eliot and Ezra Pound rushing through Europe collecting artefacts from the museums before the collapse. Paul Valéry paints the image of a European Hamlet in the graveyard of European culture, picking up the skulls he at first does not recognise. This one is Leonardo’s, that one is Leibniz. What is he to do with these skulls? If he abandons them, will he be abandoning himself?

The solution to the cultural impasse is revalorisation and re-appropriation, as well as innovation in the arts. To say that the European artist finds himself emerging from an intellectual heritage is not to say he or she must be burdened by it, or reverential towards it. Indeed it is to say the contrary: it is to say that the European artist must move from where he finds himself, taking account of where that is. Revalorisation and innovation are no longer opposites. The various imaginative spaces in Europe are all of them historically conditioned, as all the communities in Europe are historically conditioned. To be a European innovator in the arts is to give a reinterpretation of these conditions, albeit implicitly. If there has been a collapse of European culture – and I suspect to totalise the collapse is to go too far – then the response and the responsibility is to reinterpret European culture after the collapse. And whatever the actual state of European culture, it can no longer look only to itself for its resources. Not only have elements of European culture entered the entire world, been taken up by others, deconstructed and rebuilt, but all the world has entered Europe: every god of almost every culture the world has known has left some traces here. Europe is not primarily a geographical space: it is a continual attempt to give some value to its own history. Mnemosyne is the mother of the muses, and the family of the muses is more diverse than ever before.

The predicament of the European Hamlet can be generalised to encompass the contemporary spirit of Europe: at an impasse, always in a ‘period of reflection’, nervous, hesitant. All that I have said suggests that the role of the artist in Europe is fundamental for moving beyond this. The European legislator has only the resources he is rendered by those who care for the imagination. He or she has the diverse histories and traditions of Europe – which implicitly involve all the world. The legislator has the fears and hopes of the diverse peoples in Europe. But these can only be employed to govern positively if they are nurtured into a healthy shape. If not, the legislator relies only on force. The engagement of the artist is precisely here: the artist carries the responsibility for the care of the imaginative resources of the Europeans, the only means by which a European community can be built. This engagement is fundamentally political in the sense of continually re-generating a European polis, of re-generating European ways of living together. This imaginative re-generation can only take place at a European level, in contemporary Europe, because all the potential substantives around which communities can be built have been shown to fail. From now on communities can only be built as ways of carrying on, as ways of striving and aspiring: for us, under these skies, Europe as an ideal describes these ways.

The political engagement called for is therefore more fundamental than left-or-right surface distinctions in political programs. It is much commented that the surface distinctions of political programs are increasingly only a façade, and that no real political choices remain. In so far as any real modern political program relies both on an interpretation of history and a project for the future, all that I have said suggests that it is only by the kind of cultural engagement here advocated at the fundamental level that these choices will reappear.

If the meaning of political engagement in the arts for Europe is now at this fundamental level, it will nevertheless be articulated and realised with respect to particular conflicts and political causes in particular places at particular times: be these at the level of immediate human survival or human rights, or be they intellectual and artistic. It is by definition impossible to speak for all of Europe, for all time. Therefore the artistic engagement that will contribute to the generation of a European polis will be variegated through different levels of generality: from geographically highly specific conflicts to issues that concern directly the whole world. But at each of these levels these causes can be fought for as a European act by Europeans. To say that is just to say that Europeans, inescapably caught up in their own history, engage politically as Europeans.

The calls for a ‘European soul’, for ‘culture’ in Europe from the political classes are often naïve and sometimes obfuscatory, but they are consistently present and more and more loudly heard. Like all things in modern Europe, that presents a huge opportunity as well as huge dangers. The huge dangers are that ‘culture’ once again becomes understood as something ‘pure’ and exclusionary, and Europe falls back on itself and fully collapses; the huge opportunity is that Europe can re-imagine itself as a community based on justice and inclusion. The opportunities are there to be taken: Europa is still just about visible ahead of us. Perhaps if we lose sight of her we will be lucky enough to find another guide, but if we are not it will be our own fault.