Justin Beaumont and Christopher Baker on dismantling ‘secular’ and ‘faith-based’ dichotomies towards a radical new imagining of decolonial postsecularity.

We argue for a decolonial perspective on postsecularity that recovers lost knowledges of discriminated people for transnational social justice. Our approach prioritises a granular, ethnographic engagement with the discourses, experiences and activisms of people displaying and articulating diverse identities, values, and worldviews across difference. Authentic holistic reconnection drives new progressive political spaces of hope, justice and solidarity featuring actors outside Christian and Western secular contexts that bridge material and symbolic culture.

This article has been written under the dark shadow of the horrific violence that has escalated in and around the Israeli controlled borders of the Palestinian Gaza Strip in October 2023, triggered by Hamas’s bloodiest ever military blow to Israel and coupled with fierce Israeli reprisal bombings (see Figure 1). These atrocities represent the latest eruption in a vicious circle of carnage that has afflicted these territories for 75 years since the Nakba of 1948.

Whether talking about these latest conflicts in Israel-Palestine, the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War and captured Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk regions, the repression of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, China, or the mass exodus of Armenians from the Nagorno-Karabakh disputed region in Azerbaijan, these struggles, acts of ethnic cleansing and human rights abuses share colonial origins.

Within Europe, for example, the power of financial capital has been concentrated in the German dominated Frankfurt banks, the German Federal Bank and the European Central Bank. These institutions have held European peripheral economies – Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Ireland – in a form of neocolonial debt bondage through a number of government and bank bailouts since 2010.

Greece’s sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial calamity resulted in austerity measures that deepened poverty and immiseration, precipitating a humanitarian crisis for millions of Greeks. Alongside the 2023 heatwave and devastating wildfires, the country’s government corruption, discrimination against immigrants and minorities, and deplorable conditions for irregular migrants and asylum seekers, continue to afflict the people.

Dreaming of the future, only a progressive decolonial politics that brings together people from diverse walks of life, ethical worldviews and political persuasions can recover lost knowledges in the quest for transnational social justice, lasting peace, and socio-environmental harmony.

Definition of terms

“Coloniality” concerns a structure of normative principles, values and practices that found western modernity and generates forms of exploration, extraction and domination of being, seeing, doing, thinking, feeling and acting. Whereas colonialism denotes the long-term political arrangements that govern these practices, coloniality refers to the logic, culture and structure of the modern world-system.

‘“Coloniality” concerns a structure of normative principles, values and practices that founds western modernity and generates forms of exploration, extraction and domination of being, seeing, doing, thinking, feeling and acting.’

“Decoloniality” is a way for us to re-learn knowledges from certain peoples, cultures and environments that were absent or forgotten by forces of modernity, settler-colonialism and racial capitalism. Drawing on the thinking of people like Fanon, Césaire and Spivak, among others (see Figure 2), the term means an intentional, holistic commitment to ourselves and respect towards the wholeness of mind, body and soul of other people in their cultural, ethnic, racial and belief differences.

“Postsecularity” refers to the stimulation of multiple ethical values arising from new relationships between people of diverse faiths and secular worldviews. Re-use of a secular, public building by a faith-based organisation, to provide social and emotional support and shelter for homeless and insecurely housed people in cities from diverse social, cultural, religious and no-faith backgrounds, would be an example in practice (see Figure 3).

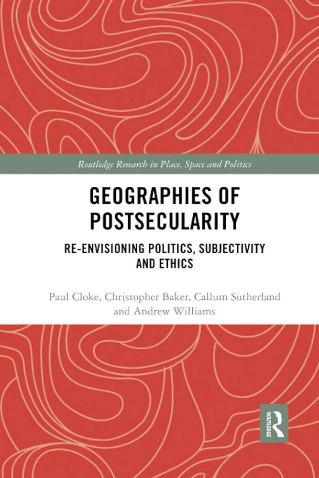

Around the same time, Geographies of Postsecularity highlighted the variations in postcolonial readings of postsecularity outside the Christian/ secular/ Western nexus (see Figure 5). The authors defined postsecularity as ‘a context-contingent bubbling up of ethical values arising from amalgams of faith-based and secular determination to relate differently to alterity and become active in support of others by going beyond the social bubble of the normal habitus’ (p. 3) with case studies from Egypt, India, Philippines and Russia.

In the aftermath of FACIT, the subsequent Horizon 2020 bid (ENLIGHTEN) in 2015 provided the material that culminated in the forthcoming Enlightened City. While fully aware of the historic colonial, rational humanist “Age of Enlightenment” connotations of the term, we seek to deploy the distinct notion of “enlightened” as spiritual awareness and recognition of radical difference. In this sense, the term embraces interculturality and the tensions between and limits of universal values and identity politics.

All along we shared the intuitive belief that something new was happening. The research agenda we now propose brings postsecularity to ground level. At the beginning we were hindered by a lack of appropriate theoretical tools and conceptual terminology to grasp precisely the nature and meaning of the empirical changes felt around us. The search for spirituality and ethical values provided the avenue for examining the changing roles of religion and secularism in contemporary societies.

Towards an enlightened city

Deepening research into the faith groups in cities, the Faith-Based Organizations and Exclusion in European Cities (FACIT) project (2008-10) critically examined the value of the “F-word” in tackling, combating or mitigating poverty, exclusion and immiseration in diverse European urban areas. Inspired by a longstanding interest in Latin American liberation theology, a crucial component of decolonial theory, the research set out to address faith groups in relation to non-faith actors, despite critical urban theory and secular humanist intellectual moorings.

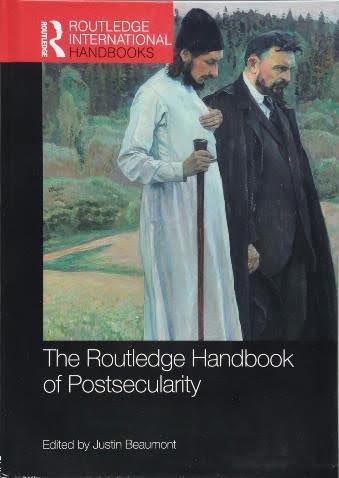

Similarly, Manav Ratti’s landmark work The Postsecular Imagination has addressed from a perspective of postcolonial literature the potentials and limits of secular and religious thought outside the West. The interaction of postcolonialism, literary studies and decolonial thought informed the Routledge Handbook of Postsecularity that brought philosophers, theologians and social scientists together (see Figure 4).

Emerging discourses, experiences and activisms

Recovering lost knowledges for transnational social justices requires appreciation of three areas of interconnected enquiry. Specifically, we refer to the material and lived out expressions of discourses, experiences and activisms arising from new coalitions and expressions of partnership and solidarity across difference in response to issues of trauma, injustice and oppression.

An example of a changing secular discourse, for example, emerges in pioneering work by scholars at Goldsmiths, University of London who are trained in counselling and therapeutic techniques within a Freudian psychoanalytic framework. Their assessment of that tradition is that it is no longer fit for purpose within the current challenges for human and environmental wholeness.

New directions in psychoanalysis around the concept of re-wilding capture new discourses that we are seeking to unearth, because it also opens new spaces of material decolonized postsecularity and new practices. Our Goldsmiths colleagues identify several new intellectual and practice-based frontiers of what we might call a decolonial postsecularity:

- Poetics of the psyche;

- Breathing in psychoanalysis;

- Wild space of thought;

- Occult feminisms;

- Ecological unconscious;

- Psychoanalysis’s wild thoughts;

- Depth psychology and deep ecology;

- Magical instinct and discursive logic;

- Animal magnetism, wild attractions;

- Queer ecologies, animalities, desires;

- Shamanic dreaming and animal metamorphose.

“New directions in psychoanalysis around the concept of re-wilding capture new discourses that we are seeking to unearth.”

The spatial and specifically urban cultural connotations of psychological and psychoanalytical inquiries would add original insights into what has been depicted as particular spaces, subjectivities and practices of postsecularity. The approach would relate sympathetically with Ankhi Mukherjee’s (see Figure 6) Unseen City, a humanistic encounter with the psychic lives of dispossessed people in Mumbai, London and New York.

Nirmal Puwar’s research, also at Goldsmiths, deals with spatial-linguistic experimentation through re-routing of established narratives of space, including consecrated spaces, such as Coventry Cathedral in the West Midlands of England. The project “Noise of the Past” was sparked by her own family’s experience, including her father and uncle, who as members of the Commonwealth fought for Britain in the Second World War.

The project attended to the civic and national erasure and amnesia of their presence and of countless others during WW1 and WW2. Puwar commissioned the composer Francis Silkstone for a postcolonial “War Requiem” featuring a poetic dialogue in Urdu between her father and his grandson. Activating a call-and-response methodology, the musical score was put to poetry by Nitin Sawhney and then made into a film by the director Kuldip Powar, opening up, re-routing and extending how war and memory are considered.

Puwar’s (2023-24) latest research returns to Coventry Cathedral and adds an historical and genealogical approach to explore the building’s archives. This exploration is designed to show previous innovative multicultural engagements might provide inspiration for new artistic and curated works and inspire material practices and imaginations of what a civic cathedral can become. For example, Ravi Shankar performed in the cathedral in 1968; Duke Ellington performed in 1966; there was a controversy over John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s living sculpture of two acorns disqualified from entering a prestigious sculptural exhibition in 1968; a service for Martin. Puwar reveals several examples in this vein.

A third case study lies in the attempt to reimagine liberation theology. This endeavour sees liberation theology reframed in line with the new viscerality of police, state and urban violence resulting in the oppression of young black and brown bodies of colour and gender. The tradition of liberation theology emerged in the late 1960s in Latin America, riven through with the most egregious experiences of colonialism, dictatorship and radical social and economic disaffection. The approach combined radical prophetic Judeo-Christian traditions with Marxist and other secular sociological critiques for the liberation of oppressed people (see Figure 7).

The movement energised both Christian theology and left-wing politics into many social movements of grassroots protest across the Global South that are still picking up faint echoes in the 21st century in events like the Occupy movement of 2011, with its deep critique of neo-liberal capitalism and its call for the radical redistribution of resources and opportunity.

A new generation of theologian-activists, however, question whether previous models of liberation theology are sufficiently robust to speak into the anger and violence now being perpetrated on the bodies of the poor and the “Othered” by authoritarian regimes across the world.

Some thinkers and activists reflect that the killing of Michael Brown and subsequent uprisings in Ferguson which sparked the Black Lives Matter movement mark a change in existential threat that the cohort associated with the civil rights movement struggles to engage with culturally and politically.

According to some trajectories in this analysis, the movement for Black Liberation has been co-opted into the American Empire that was, and continues to be, American exceptionalism. The rise of Black American elites, culminating in the election of Barack Obama as the first Black President of the United States, and the rise of Black ‘civil rights entrepreneurs’ has not led to any reductions in the numbers of Black and Brown people living in extreme poverty or indeed the number of police murders.

For others who still work within the faith-based racial justice system there is desire to reconnect Black Liberation theology more explicitly with the rage and thirst for justice, dignity and recognition experienced by additional “Othered” groups.

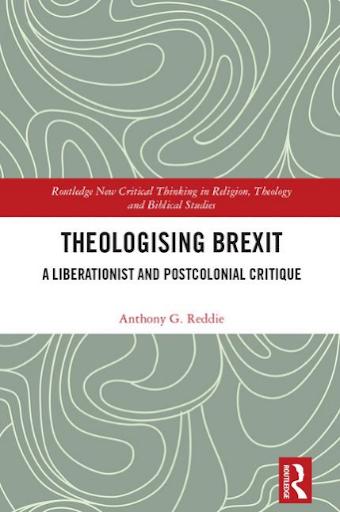

Anthony Reddie’s Theologising Brexit, for example, presents a prophetic, liberationist and postcolonial approach to Black theology that critiques White entitlement and parochial nativism in Brexit Britain, within wider debates on transformative education, critical pedagogy and challenges to Whiteness (see Figure 8).

Finally, the growing presence of spiritual environmental activism within mass protest on climate change is another area for our research. Faith groups and practices associated with faith traditions such as prayer, meditation and open-air masses outside the “spaces of Empire” (such as fossil fuel multinationals and government offices) are now at the heart of nonviolent protest events organised under the umbrella of Extinction Rebellion and other climate change movements (see Figure 9).

At the centre of both religious and secular critiques of the Anthropocene within the climate justice movement is the recognition of the colonial project of empire that historically has treated ecosystems as an endless source of growth and exploitation.

Conclusion

Arguing for a granular, ethnographic engagement with discourses, experiences and activisms we believe that the search for an authentic holistic reconnectivity, that emerges out of a deep despair at, and profound mistrust of, “politics as usual” is what is driving what these case studies are pointing to: namely, a new enlightened approach to political alliance formation. Immense difficulties stand in the way of this agenda. Responding to the demand for independent indigenous research, voice and leadership of cross-cultural teams would be of paramount importance throughout the proposed case studies that would aim to recover lost knowledges for transnational social justice.

These instances attempt to discover new alliances and expressions of solidarity across difference that include at their core a willingness to reject solid binaries between religious and secular identities. All these arenas emerge as a response to the trauma of the present age that is predicated on racialised, misogynistic, therapeutic, homophobic or “Anthropocenic” violence. They seek a profound rethinking of the importance and vitality of intersectionality, authenticity, wide-ranging empathy and the search for new and alternative expressions of belonging, community and the shared search for justice and dignity for all.

“All these arenas emerge as a response to the trauma of the present age that is predicated on racialised, misogynistic, therapeutic, homophobic or “Anthropocenic” violence.”

In the course of these searches, new practices are already beginning to appear. Based on innovative and experimental experiences of progressive solidarity and partnership, involving otherwise largely silenced voices, these practices will place previously lost knowledges centre-stage and contribute to a radical iteration of a material decolonial postsecularity.

Justin Beaumont is an independent scholar and writer originally from the UK and based in Mannheim, Germany.

Christopher Baker is William Temple Professor of Religion and Public Life at Goldsmiths, University of London, United Kingdom.

Further Reading

Beaumont, J. (ed.) (2018) The Routledge Handbook of Postsecularity, first hardback edition, 2020 paperback, London/ New York: Routledge.

Césaire, A. (2001) Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, English edition, ed. Annette Smith, trans. Clayton Eshleman, first published in French, 1939/ 1947/ 1956, “Cahier d’un Retour au Pays Natal”, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Cloke, P., Baker, C., Sutherland, C. and A. Williams (2019) Geographies of Postsecularity: Re-envisioning Politics, Subjectivity and Ethics, London/ New York: Routledge.

Fanon, F. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth, preface by Jean-Paul Sartre, originally published 1961, translated by Constance Farrington, London: Penguin Books.

Gregory, D. (2004) The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq, English illustrated edition, London: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gutiérrez, G. (1988) A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics and Salvation,: Ossining, NY: Orbis Books.

Latour, B. (2017) Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, translated by Catherine Porter, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Puwar, N. (2011) ‘Noise of the past: spatial interruptions of war, nation, and memory’, The Senses and Society, 6(3): 325-45.

Ratti, M. (2013) The Postsecular Imagination: Postcolonialism, Religion, and Literature, London/ New York: Routledge

Reddie, A. G. (2019) Theologising Brexit: A Liberationist and Postcolonial Critique, London/ New York: Routledge.

Said, E. W. (1978) Orientalism, New York: Pantheon Books.

Spivak, G. C. (1988) ‘Can the subaltern speak?’. In Nelson, C. and L. Grossberg (eds.) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 271–313.

Varoufakis, Y. (2021) Another Now: Despatches from an Alternative Present, London: Vintage.