by Nicolas Bourdeaud & Maxime Ollivier

Citizens’ Assemblies are a participatory democracy tool that has been used more and more in recent years in France. As activists fighting for democratic renewal, we are interested in the sometimes mixed impact of these tools, which seem to us to hold great promise. This short article considers Citizens Assemblies (CAs) at three different levels in order to have a large overview of this Deliberative Democracy tools and its outputs in France: at the national level with the Citizens’ Convention on Climate (CCC) – years 2019-2020, the regional one with the Occitanie Citizens’ Convention (OCC) – year 2021, and at city-level with the Poitiers Citizens’ Assembly (PCA) – year 2021.

Here are a fews questions we’ll try to answer to get an overview of these three CAs’ outputs: did they have quality and coherent achievements? What has been the response from both the public authorities and the population? To what extent have the measures proposed been implemented and how? Have the participatory processes and the implementation been monitored and evaluated, and how?

Before going any further into the analysis, here is a brief recap of what can be said on the main clues and indicators that we considered relevant to have an overview.

| Citizens’ Convention on Climate | Occitanie Citizen Convention | Poitiers Citizen’s Assembly | |

| Question asked to the citizens’ assembly | “How can we reduce Greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030, in the spirit of social justice?” | “Within the framework of the major areas of intervention of the Regional Council, what are your expectations and the concrete measures that you recommend to improve the life of the inhabitants of Occitania, in the current context and to prepare the future?” | Co-construct the municipality’s roadmap on digital responsibility. |

| Outputs | June 21, 2020149 proposals classified in 5 parts, with, for each proposal, the mode of application foreseen by the citizens (referendum / organic law / parliament) | October 3, 2020 a document bringing together: – “expectations for a transformed region”- 52 priority measures – also included nearly 300 proposals debated during the working days. | July 23, 202145 concrete proposals to make digital tools more accessible and sustainable |

| Responses | – Political: June 29, 2020: Macron refuses 3 propositions (famous “jokers”) on 149 measures. – Media: Heterogeneous coverage over time. CCC is most often presented as a “political object” rather than a democratic experiment. – Population: measures massively supported by French population , but its scope and functioning are not understood or well known. | – Political: respect / presence of Carole Delga as the president of the region, for the last session / next step anticipated: Regional Council. – Media: quickly and little covered by both mainstream and independent media for the last session. – Population : no data. | – Political: respect and support, coherence with the Mayor campaign program. – Media: simple and precise, mainly covered by LaNouvelleRépublique – Population: a broader audience was involved in conferences and debates. |

| Effective implementation | April-June, 2021: the climate law has largely “edulcorated” citizens’ measures. Only 15 propositions, less than 10%, were effectively implemented. | 45 priority actions of the convention, along with 155 proposals, were integrated into the GND adopted by the Regional Council on November 19, 2020. | No data |

1. Citizens’ Convention for Climate (CCC)

The work of the conventioneers is widely recognized as a huge and quality package of efficient measures. The citizens had one main requirement: the 150 measures are a package, and make sense if they are applied together. We come back here on some elements that show the inappropriate and disappointing response of the French government and media to this precious production.

“Unfiltered”

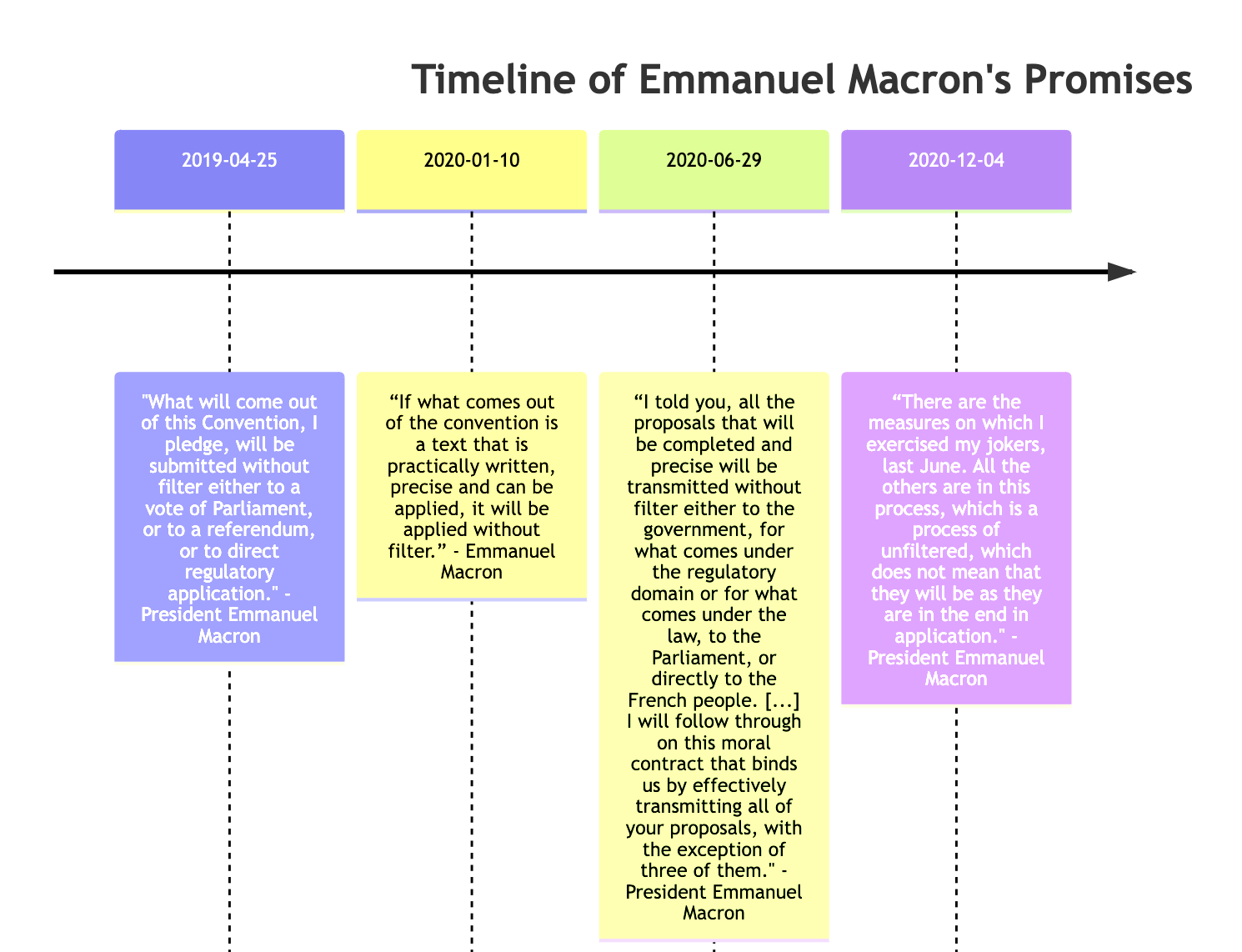

A few years after the first announcement of “unfiltered” by Emmanuel Macron, some have forgotten this commitment from Mr. Macron, the conventioneers will undoubtedly remember it forever. Here is a brief recap of how the public commitment of President Emmanuel Macron has evolved – which well symbolises both the political response and the lack of consideration of the propositions of the CCC:

The “Climate Law”: “Act to combat climate change and strengthen resilience to its effects”

After the Citizens’ Convention On Climate, a law has been presented to the parliament: the “climate law” was supposed to integrate CCC’s mesures. The debate has been restricted by the president of the commission, the deputy Laurence Maillart-Méhaignerie from the presidential majority at the national assembly. While only 46 measures had been inserted in the text of the bill, she refused more than a quarter of the amendments, pretending they were not linked to the subject (using article 45 of the Constitution), even when the amendments took up proposals from the Convention itself. The appreciation to declare an amendment “inadmissible” is left to the total authority of the president of the commission – of the concerned law.

Two years after the Citizens’ Convention on Climate, among the 149 proposals of the CCC:

- 18 have been taken up “without filter”.

- 26 were not taken up at all

- The rest of the measures were only partially taken up.

The opinion published by the High Council for the Climate (HCC) on February 23rd, 2021 is clear: the bill lacks a “strategic vision” and the strategic approach of the National Low Carbon Strategy (NLCS) should be integrated into the bill, supplementing it with new measures, especially on building renovation. According to the HCC, the scope application of several measures is “restricted”, and covers an insufficient share of greenhouse gas emitting activities.

This reduction of the ambition of the CCC through the climate law and the visible disrespect of the citizens and their work by President Emmanuel Macron and the presidential majority at the parliament has led to significant demonstrations: more than 160 demonstrations have been held throughout France on 9th May 2021, after the appeal to demonstrate had been signed by over 690 organisations. These demonstrations will remain famous for the image of this big white sheet, with a note on it, 2,5/10, which is the grade given by the citizens of the CCC on the effectiveness of the climate and resilience law to meet the initial objective of reducing GHG emissions by 40%.

Thus, even if the CCC, its members and their production had been able to arouse a great support from the population, the media and even more the political treatment have been very rude, and the implementation of the measures proposed can be evaluated around 10-20% today. Regarding the monitoring, neither the citizens, nor the HCC, nor the demonstrations, succeeded in making the government bend, to take advantage of the historic opportunity to respond to climate issues while propelling a democratic innovation that would have created consensus among the population.

2. Occitania Citizen Convention (OCC)

The final session of the OCC was carried out on October 3rd, 2020. During this session, “the expectations for a transformed region”, a kind of global trend spirit, were enacted and officialised, and more importantly, the 52 priority measures.

Interesting to see that the sessions have been organised in different cities (Toulouse, Montpellier and Carcassonne), thus participating in the communication around the OCC, and eventually to the global support of people of Occitania to the OCC. The CCC had paved the way for this support, and left time to Carole Delga and her team to learn from President Emmanuel Macron’s mistakes. Thus the next official steps were already anticipated since the beginning of the CA. This is one of the reasons why 45 priority actions of the convention, along with 155 proposals, were integrated into the Transformation and Development Plan adopted by the Regional Council on November 19th, 2020. Another reason is that the GND had been worked a lot before, and the work of the citizens had been prepared, almost drafted. We can observe a bit of disappointment among the organising team because, contrary to the CCC, the measures are quite large, and are consequently less powerful, and easier to reuse by the political authorities. Besides, an article from the very ecologically committed newspaper WeDemain rightly notes the coincidence of the implementation of the OCC with Carole Delga’s political re-election agenda. This seems to be in line with the testimonies of some people who have worked with her at the region: reelection objectives as soon as she became head of the region, and controlled communication to achieve these objectives. The OCC is undoubtedly a part of this strategy.

3. Poitiers Citizen Assembly (PCA)

As with other CAs, one of the successes of the PCA is the active participation of the members of the CA. As with the OCC, the next political steps of the measures proposed by the members were clear even before the beginning of the participatory process. So, we can, of course, note a great support from the political power in place, and also a support of the participants of the conferences organised aside of the PCA. Indeed, in an approach of transparency and accessibility, the City of Poitiers has done two things, trying to enlarge the perimeter of the people involved in the process :

- First, the city has joined forces with two news media

- Second, conferences with experts have been organised, to bring the subject of the PCA to the attention of as many people as possible.

Another point that is very important to point out regarding the PCA: the City of Poitiers has been accompanied by the Commission National du Débat Public (CNDP).

Conclusion

The comparison between the objective of the CCC and its effective implementation and monitoring brings out the question: how can CAs be more powerful? The Occitania and Poitiers conventions give some clues to answer this question: today, most of the impact of CAs depends on political public commitment to support them and ensure since the beginning that citizens will be the decision-makers, and not simply consulted.

By comparing with Citizens Assemblies in other countries, Dimitri Courant’s recommendations are also going in the way of a need for a public commitment: “Cherry-picking and watering down of the CCC’s recommendations show the need for a tighter coupling between deliberative panels, the political institutions, and the broader citizenry. A commitment from the start to a referendum on the whole citizen report, similar to the case of Canadian citizens’ assemblies, could have been a way to avoid those issues. Furthermore, the Irish case shows the importance of a referendum for the mini public’s propositions to be democratically approved and implemented.”

Looking at the three French Citizens’ Assemblies studied here, one of the solutions is to improve the public commitment to one-off CAs. Another one could be to institutionalise CAs as a process in which public commitment, implementation and monitoring are framed and then, can truly have an impact in the real world. But the institutionalisation of such a deliberative process as CAs necessarily has limits: the risk of abuse in the use of complex and expensive processes in order to find legitimacy rather than in the aim of truly improving democracy. The institutionalisation also chimes with the lack of agility in the design and the temporality: “There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach; it depends on the context, purpose, and process.” (OECD, 2020). Since every situation will lead to a different approach, in implementing deliberative democracy we need to find a way to combine institutionalisation and innovation in the creation of the Citizens’ Assembly. There are criteria that can reinsure the solidity of a process, but finally isn’t a powerful CA the one that is able to ponderate different criteria regarding the context? Ultimately, the risk is having no one holding the responsibility in the decision anymore and that there is no actor to fight for the right and fair implementation of proposition made by CAs participants: using Citizens’ Assembly as an institutionalised process can lead to political cowardice and a less intense follow-up by political leaders.

Nicolas Bourdeaud is committed to ecological, democratic and social justice. He has a degree in energy transition engineering (ISAE-Supaero) and political science (Sciences Po Paris). After working on mobilisation for the Primaire Populaire, and writing a research dissertation on Syntropic Agroforestry, he is now focusing on the 2026 municipal elections, for which he is initiating, training and supporting citizen and participatory lists on collective intelligence, municipalism and citizen mobilisation with Fréquence Commune. In Grenoble, he is particularly involved in the Grenoble Alpes Collectif to win the elections and set up a citizens’ assembly to discuss the city’s budget.

Maxime Ollivier is an activist for social and climate justice. Climate demonstrations, advocacy, civil disobedience with Extinction Rebellion, electoral campaigning with La Primaire Populaire for the presidential election in 2022: he tried out a number of modes of action before turning to art as a mobilisation tool with the Le Bruit Qui Court collective. He is the author of two books published by Actes Sud: Basculons dans un monde vi(v)able (2022) and Vivre avec éco-lucidité (2024).