Paula Soli reflects on intersectional feminism and the harsh realities of claiming space in a world shaped by coloniality

It is not unusual to notice that the words diversity, equality and inclusion are on everyone’s lips at the moment. It also seems that this inclusive agenda only comes from minoritised groups who reject systemic discrimination because they want a fair, real and effective representation in all societal spheres.

Doesn’t sound too bad, does it? But what are we currently facing when we try to create a more diverse and inclusive vision? Forced inclusion, indoctrination; treated as a threat.

But a threat to what? Well, we are a threat to the status quo, to “normality”, to whiteness, to cisheteronormativity, to colonial practices and ideals among other things. My very existence is seen as a threat. Our existence (appealing to minoritised groups) has the potential to threaten what is grudgingly defended.

Because it has been decided that my body, my afro, or my life are political causes. Isn’t it ironic? And we assume it, we assume the extra work that we have to do, the search for excellence, the “I am not like the rest”, the defense and survival mechanisms, to unseat ourselves from the “bad heap”, and with luck; perhaps with a little self-love and community love, we will manage to make peace with ourselves and return to that “bad heap” in which we recognize ourselves. Weaving networks from the pain, and trying to free ourselves from the common rage.

My interest in diversity is, in a way, a given. It is intrinsic, implicit, and I could even consider it as obligatory, imposed. To talk about racism, sexism or other discriminations, we only approach those who suffer from them, and of course, those are the only people legitimized enough to speak in first person about personal experiences that should not be counter-argued.

However, social justice encompasses cross-cutting issues, from which no one is exempt: whether to their detriment or benefit. If there are people who benefit per se, why aren’t they involved in change-making? They are given the wild card of looking the other way because it doesn’t touch them closely. How easy, isn’t it?

With this I want to state that we cannot, nor should we, champion each and every one of the existing struggles, especially those that we do not experience, but it is our duty to be informed when other people’s rights are violated. But for that to happen, I believe that a voluntary critical exercise is needed; but again, even being an activist and standing up for what we believe in is a huge privilege. Activism, to a certain extent, is still a privilege.

I am writing this article for the European Alternatives project I am involved in called Youth Movement and Campaign Accelerator. It is a proposal that brings together young activists from various countries of the European Union to learn how to mobilize our local communities around participatory democratic proposals, on issues of special individual and community interest.

When I was invited to the first meeting, without even knowing if I had been accepted into the programe, my first reaction was, how diverse is this programe? I don’t know if I am going to be very comfortable in a European programe in which no people of colour participate (understanding that racial diversity, which is the part that affects me most directly as well as gender, is part of a wider range of representation that also includes sexual identity, religious confession, age, abilities, etc).

What kind of fair representation would it be of the current demographics of the region? One might somehow think that this is a “problem” that I bring upon myself, however, my answer is that I don’t actively seek to feel excluded, on the contrary, I seek to create mediated connections. To know how many people there will be who will be able to understand my experience.

Because I speak from discriminatory experiences. Not only my own, but collective. Let’s call it a defense mechanism.

There were two event organized with the programe. The first one in Paris in December, the second one in Berlin in March. At the first event that was organized in Paris, I felt comfortable to see that, visibly, there was diversity. Not just the kind that exempts minority groups from being in decision making positions. During the stay, I was able to learn about the work that other participants are doing with their respective groups in various countries, ranging from the fight against climate change, movements in favor of abortion, mental health, the visualization of bisexuality or the right to euthanasia. The aim was to learn, through workshops, how to organize a people’s assembly that would help us with our issues of concern – from identifying stakeholders to targeting beneficiaries.

During the stay in Berlin, we came together once again to discuss our assemblies, learn more about each other and our work, in a full week programe including activist workshops and exchanges. It was very interesting to see what the other participants had done, and to met new people that got involved later. As in the previous one, I felt comfortable being surrounded by people that practice collective care at a first instance. The fact that everyone was on the same page made it easier to connect without having to be wary about people’s reactions. In effect, this is what happens in some activists movements; there’s the advantage of comfort because you are seen for what you are and, most of the time, there’s no need to go any further explaining your struggles. They understand, or are willing to do so.

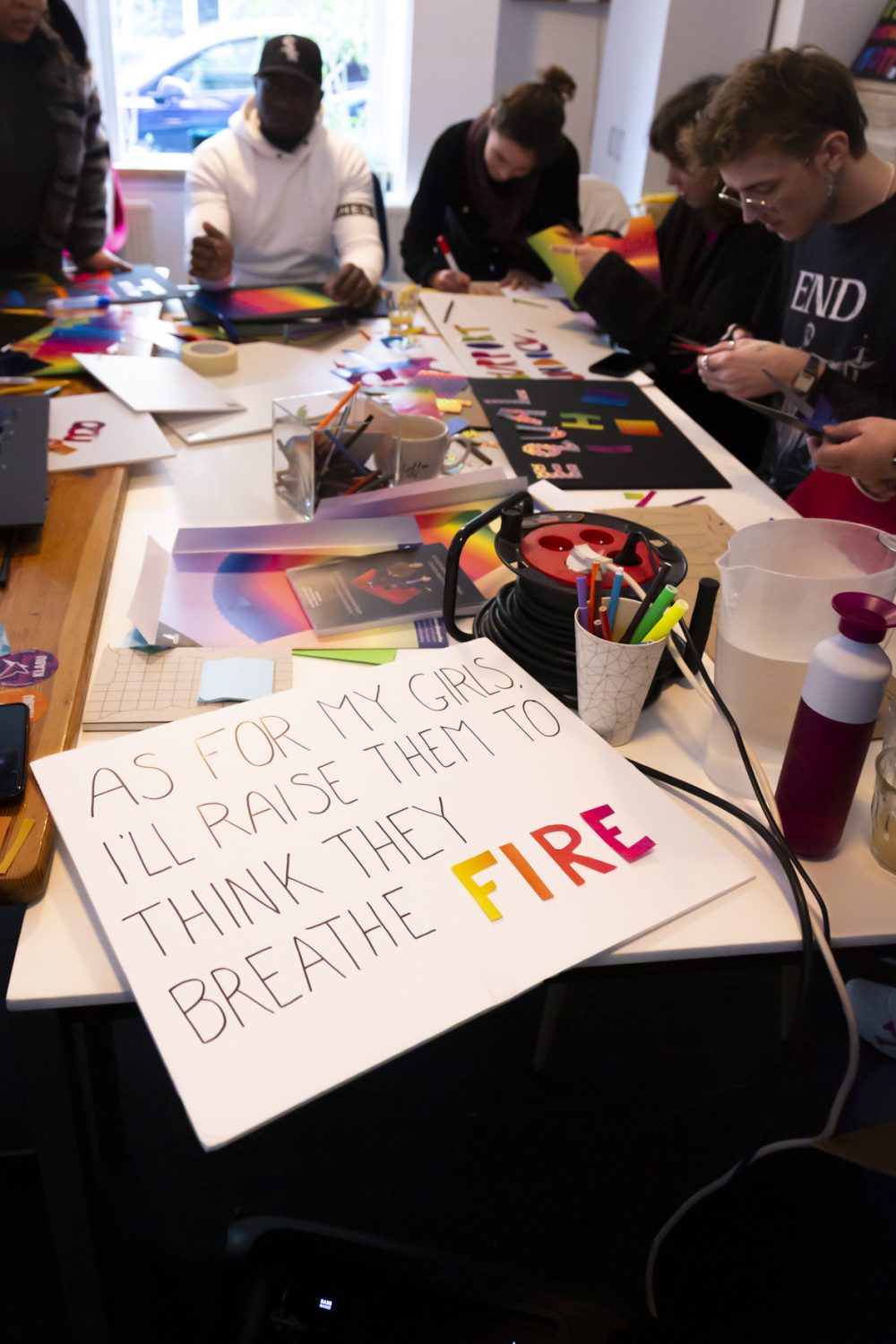

With the help of the Here to Support team in Amsterdam and friends, I organized an event in Amsterdam on 5 March in preparation for International Women’s Day. The event was entitled: Feminism, Women and Migration. The aim of the event was to highlight the importance of having an inclusive and intersectional view on feminism, as there is still a clear under-representation of POC and migrant women’s groups. Undocumented women shared their experiences with the rest of the participants, who, by being there, were showing an interest in the issue.

However, how can we influence a more humane migration policy if the people who can exert that weight are not interested, or simply, as it is an issue that does not concern them, they can use their privilege to look the other way? Returning to the idea of creating more diverse, equitable and inclusive spaces, how can we do this if the people who hold the most power do not share any discrimination against the people who “should” be included?

To continue with the irony, there would probably be noticeable changes in this area if people from privileged groups did something, however small. That’s just the way it is.

I wish we could get past the stage of asking people who suffer any kind of oppression/ discrimination why diversity is important, to stop asking why we have the right to step out of the margins and write our own stories. Because that would imply that we are only being done a favor by being given a space to speak. No, that space belongs to us as much as it belongs to anyone else, but it just so happens that now it’s up to us to prove it.

So I appeal to individual critique to think about what space we should occupy, and what our role in it is.

And if we are visible, and if there are more of us, and if more and more people see themselves represented, as is the real reflection of our society, and if we make people uncomfortable, so be it.

Let’s continue to make people uncomfortable.

Paula Soli is an activist from Barcelona interested in campaigns addressing decolonisation, antiracism, diversity-equity-inclusion, feminism, queerness and migration. She is a participant on the European Alternatives Youth Movement and Campaign Accelerator Programme.