Enikő Vincze calls for a return to housing as a social good

Housing is a complex phenomenon produced at the intersection of social and economic policies, but both in academia and in politics, it is conceptualized and debated as a rights issue or an economic matter of production/consumption/investment. In this paper, I discuss the historically shifting connections between these two dimensions while also relating the production and distribution of housing to alternating industrial relations.

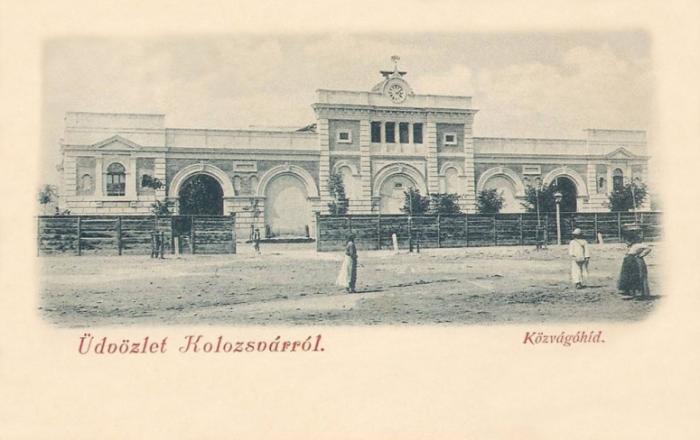

Credit: Archive Transylvanian postcards from the past, Erdélyi képeslapok a múltból, https://kepeslapok.wordpress.com/2011/10/22/kolozsvar/.

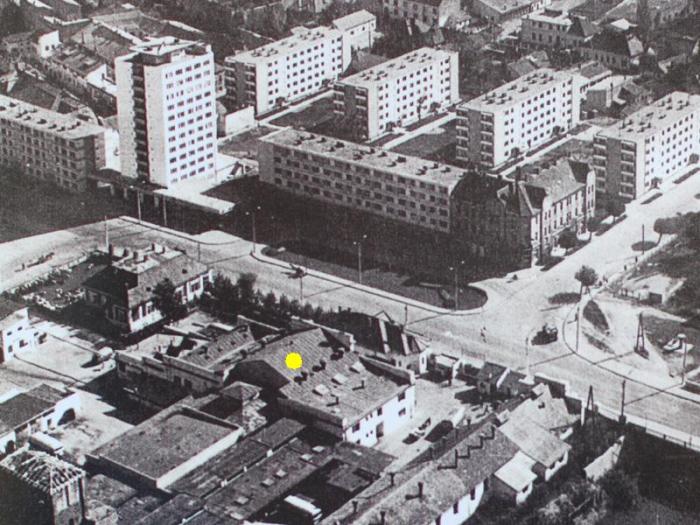

Credit: http://wikimapia.org/29210696/ro/Fostul-Abator#/photo/4703659

I am writing this piece of analysis in Cluj-Napoca, a city that, in the past seven years, has become the most expensive locality in Romania from the point of view of the housing market. In the past three decades, changes to the political economy were built across the whole country on the “creative destruction” (Harvey, 1982) of state socialism, including its economic and housing regime. Therefore, in the first two sections of the article, I will address housing as a right and housing as an economic matter in the context of these transformations. In a third step, I will demonstrate that the transformation of former industrial platforms into assets and sites for new real estate development contributed to forming a new housing regime that prioritizes the interests of capital accumulation and neglects housing rights. Most importantly, in this article I will argue that after three decades of capitalist transformations in Romania when housing became accessible predominantly through the market, there is a political imperative to prioritize housing as a social need and human right, and subordinate the concerns of capital accumulation to this perspective.

Housing as a socioeconomic right

In Romanian state socialism, housing was not recognized as a constitutional right, while the right to personal property (among others, to home) was so recognised. Nevertheless, the governmental policies aimed at providing a home to everybody linked to employment, and the system elaborated and implemented a mixed housing regime where the residential units in the property of the state or state-owned enterprises were complemented with a small amount of cooperative housing and a significant percentage of homes in personal property. During state socialism, personal property was controlled by the state to avoid its transformation into an instrument of creating/increasing inequalities (Vincze, 2022).

After the right-to-buy laws from the 1990s started to make their effects in parallel with the privatization of the whole economy (see Figure 1), and due to all the governmental measures sustaining the private production of private homes, the housing market, the privatization of the banking system and the appearance of investment funds, the access to an adequate home became dependent on people’s financial capabilities.

The Housing Law 114/1996 talks about the right to access a home, not the right to housing. In addition, while decentralizing housing production, this law did not provide any means by which the local public authorities could have been encouraged/motivated/obligated to respond to local social housing needs. Moreover, even the Romanian social legislation promising to protect the right to a home for vulnerable groups, children, or people with disabilities, does not imply mechanisms by which the public authorities obligations could have been translated into concrete measures in this domain.

Housing as an economic matter

The political objective of state socialism – to provide everybody with a home according to their employment, was rooted in its concerns about assuring the necessary labor force in the cities to fulfill the plans of industrialization as a major pillar of socialist transformations in a formerly agricultural and rural country. Overwhelmed by the high number of new homes needed in this context, the state produced socially rented residences in blocks of flats and sustained the private acquisition of homes via loans provided by the state-owned savings bank at a very low-interest rate. As a result, between 1951-1989, 5,528,465 new homes were constructed in Romania. From these, as Figure 2 displays, 2,984,083 (53.98%) were made with public money (calculations by the author, based on data published in Anuarul Statistic, 1990, Romania’s Statistical Yearbook for 1990).

The percentage of homes constructed under the public budget compared to the total number of newly constructed housing units was still higher in 1990 (88.07%), when the state-owned construction companies finished the blocks of flats that they started to build before 1990 (calculations by the author, based on the data of the National Institute of Statistics). The trend of relatively high levels of this rate continued in 1991 (76.97%) and 1992 (49.84%), too; however, the state built fewer and fewer new homes and, when it did, it started to do it via private construction companies. Furthermore, the percentage of dwellings made from state funds declined radically to 6.01% in 2000 and 2.28% in 2021.

In the early 1990s, international organizations playing a role in transforming capitalism at the global level emphasized that housing is a central element for the formation and advancement of the market economy (World Bank, 1993). Despite this, policymakers did not explicitly recognize that, in due process, housing became a favored site for capital investment, and real estate development turned into an important pillar of the post-Fordist accumulation regime (Aalbers & Hofman, 2019). Therefore, policymakers do not acknowledge that such a change is responsible for the withdrawal of the state from the production of public social housing and the denial of housing as a right and social need, even if, meanwhile, they continuously implement measures to ensure the (re)production of the neoliberalized housing regime.

The transformation of industrial spaces into assets and sites for new real estate development

The transformation of state-owned industrial enterprises into commercial companies in Romania at the beginning of the 1990s opened the door for their privatization. As a result of transferring them from public to private ownership, industrial lands and buildings became tradeable assets and/or physical territories for real estate development as a business.

On the one hand, these former public goods could be traded by different means in and after privatization. For example, the state could sell its shares in these companies to Romanian or foreign firms through auctions (Foreign Direct Investment was strongly favored in a capital-weak context), and, in addition, it distributed a part of its shares between employees (MEBO method) and Romanian citizens (mass privatization). Further, companies or individuals could buy as many value coupons as they wanted from the market and use them to purchase stocks in other companies announced for privatization. Those who became majority shareholders could decide on the companies’ future, for example, on its liquidation, continuation of production, or other alternatives that seemed more profitable to the new owners. The shares could be continuously traded on the market and, at an appropriate time, by a particular owner, could be used as capital for investments into real estate with promising returns.

During these processes of investment and transaction, the exchange or market value of the former industrial assets was decoupled from the physical and social use of lands and buildings. Differently put, the industrial platforms’ real estate value, formerly part of the productive economy, granted a new significance to them by connecting them to the financial economy. They could be rented for any activity and generate rental income for the owners while their market value increased in time, so they could be sold at a higher price than the one at which they were initially purchased. Former industrial lands could be used as collateral for new loans from banking and non-banking financial institutions to be invested into anything. A former industrial company’s debt could be converted into and sold as assets, resulting in creditors becoming shareholders in the indebted company.

On the other hand, the privatized and liquidated former industrial platforms became physical territories/sites for new real estate development. The former industrial buildings could be demolished to make room for new construction with a high real estate value also resulting from the exchange value of the land. Due to changing urban regulations in a post-industrial context, the opportunities to change the function of buildings and land became a taken-for-granted potential to make profit from the former industrial platforms. Once used as sites for new real estate development for sale or rent, they created new sources for further profit-making. The latter was also dependent on what happened in the geographic vicinity of the respective former industrial platforms or the city at large, i.e., on other investments made by other private actors or by the urban regeneration programs of the local public administrations. In addition, as new real estate developments could be sold through mortgages, the former industrial platforms also generated profit for banking and non-banking credit institutions and for anyone with money to invest in real estate (institutional investors of different kinds or physical persons) or to become shareholders in real estate companies listed on the stock exchange.

Conclusion: the demand to prioritize housing as a social need and right

As demonstrated in this article, nowadays in Romania, too, “the right to housing” is dependent on people’s economic condition, and the state (or the employers) do not assume a de facto responsibility in producing and distributing social hou

sing among those who do not have financial means to provide for themselves an adequate home from the market. Therefore, housing ceased to be a right, and its acquisition became an act of meritocracy. Meanwhile, people became useful or surplus from the point of view of real estate capital depending on their ability to purchase a home from the market.

By repeating the mantra that the state lacks financial means for the production of homes, governors and experts at different levels naturally associate housing as an economic matter with the use of housing as a site of profit-making. When arguing why housing cannot be a positive right assured by the state to its citizens, they do not admit that the economic policies of housing result from political decisions about the priorities for public budget distribution. Under the cover of the apt recognition that the production of public social housing requires economic resources, the state continuously decides to use its supplies for supporting capital investment and its profit-making logic in the domain of housing, too, and dispossess itself from the instruments of assuring the right to housing for all.

Last but not least, the transformation of former industrial platforms into assets and sites of real estate development as a business illustrated the larger process of the economy’s and housing’s financialization. In its turn, the latter made housing rights completely obsolete and, even more, conditioned on one’s capacity to use their right to access housing (that the Romanian legislation recognizes) from their financial resources. In this context, the mainstream discourses and practices that naturalize housing production via real estate development are not only to the detriment of housing rights but also delegitimize the political commitments centered on these rights.

In light of the above analysis, my major conclusion is that to assure housing rights, state politics should not neglect the financial foundations of housing provision, but needs to cease confusing the latter with the transformation of housing into a site of profit-making and capital accumulation. Therefore, a new housing politics should put a new finance system at its center that prioritizes the fulfillment of housing as a social need and right.

Credit: Picture taken by the author on 21st of August 2023.

Cited references

Harvey, David (2007) [1982]. Limits to Capital (2nd ed.). London: Verso.

Aalbers, Manuel B. and Annelore Hofman (2019). A finance- and real estate-driven regime in the United Kingdom. Geoforum. Volume 100: Pages 89-100.

Vincze, Enikő (2022). The mixed housing regime in Romanian state socialism. In Money, Markets, Socialisms. Papers presented at the conference titled “Non-Capitalist Mixed Economies,” edited by Attila Melegh, Budapest, Eszmélet Special Issue: 26-45.

World Bank (1993). Housing Enabling Markets to Work. World Bank Group.

Enikő Vincze is a professor of sociology at Babeș-Bolyai University and housing justice activist at Căși social ACUM!/Social Housing NOW! in Cluj, Romania. Her recent research and publications focus on uneven development, housing inequalities and their racialization and real estate development as capital accumulation process.